Doctors, Pharmacists, and the Real Story Behind Generic Drugs

You’ve probably seen the price difference: $4 for a month’s supply of generic lisinopril versus $150 for the brand-name Zestril. It’s easy to assume the cheaper version is just a knockoff. But for providers who prescribe these drugs every day, the story is far more nuanced. Generic medications aren’t just cheaper copies-they’re regulated, tested, and widely used. Yet, not every provider treats them the same way. Some switch patients without a second thought. Others refuse to substitute, even when it’s allowed. Why? The answer lies in clinical experience, patient outcomes, and the quiet tension between cost savings and clinical certainty.

How the FDA Ensures Generics Work the Same Way

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration doesn’t approve generics based on guesswork. To get approval, a generic drug must prove it delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name version. That’s called bioequivalence. The standard? The drug’s concentration in the blood-measured by Cmax and AUC-must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand’s numbers. That’s not a wide margin. It’s tight enough to ensure the body responds the same way.

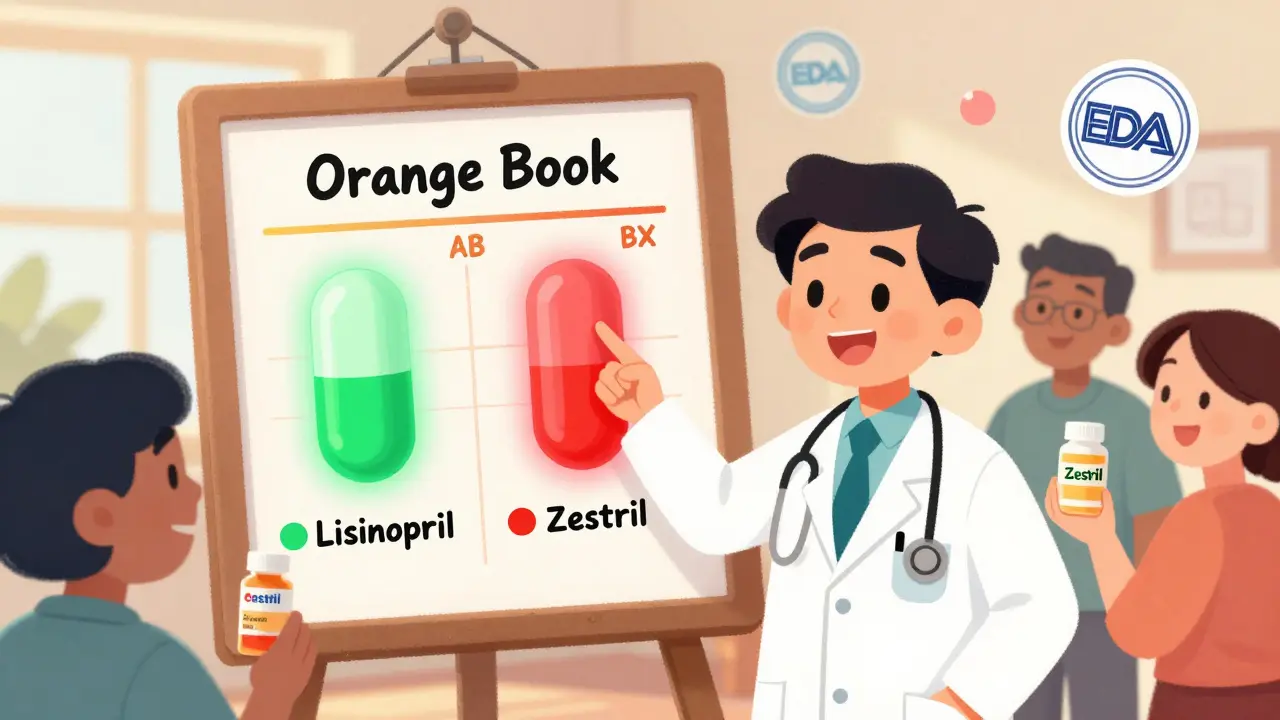

Since the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, the FDA has streamlined the process. Instead of running full clinical trials, generic manufacturers submit an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). In 2022, the FDA approved 745 generic drugs, with an average review time of just 10 months. That’s a far cry from the 36 months it took a decade ago. The agency also maintains the Orange Book, which rates drugs for therapeutic equivalence. An ‘AB’ rating means the generic is considered interchangeable with the brand. A ‘BX’ rating? That’s a red flag. It means the FDA found evidence the generic might not perform the same.

One major example came in 2016, when two generic versions of Concerta (methylphenidate) were downgraded from AB to BX after hundreds of patient complaints about reduced effectiveness. The FDA didn’t just take the complaints at face value. They tested the pills, reviewed manufacturing data, and consulted experts. The result? A public update to the Orange Book. This wasn’t a glitch-it was the system working as designed.

When Generics Work Flawlessly

For most patients, switching to a generic is seamless. A 2019 JAMA Internal Medicine study looked at 10 drugs, including blood pressure meds like amlodipine, cholesterol drugs like atorvastatin, and antidepressants like sertraline. The researchers compared outcomes between patients on brand-name versions, authorized generics (the same drug sold under a different label), and regular generics. The findings? No meaningful differences in hospitalizations, emergency visits, or medication discontinuation rates.

Providers who treat hypertension, diabetes, or high cholesterol often see this firsthand. One primary care physician in Ohio reported that after switching over 500 patients from brand-name statins to generics, not a single patient returned with new symptoms or lab abnormalities. The savings? Over $120,000 in out-of-pocket costs for those patients in one year alone.

Medicaid data from 2006-2007 showed that eliminating the need for patient consent for three common generics-atorvastatin, clopidogrel, and olanzapine-could have saved more than $100 million in a single year. That’s not theoretical. That’s real money saved on prescriptions that work just as well.

The Tricky Cases: When Providers Hesitate

Not all drugs are created equal. For medications with a narrow therapeutic index-where even small changes in blood levels can cause harm-providers tread carefully. This includes drugs like warfarin (a blood thinner), levothyroxine (for thyroid disease), and immunosuppressants like cyclosporine used after organ transplants.

One neurologist in Minnesota shared a case where a patient with well-controlled epilepsy had a breakthrough seizure after switching from brand-name lamotrigine to a generic. The patient had been seizure-free for three years. After switching back to the brand, the seizures stopped. Similar reports exist for phenytoin and carbamazepine. Because of this, the American College of Neurology recommends that generic substitution for antiepileptic drugs should never happen without explicit consent from both the patient and the prescribing provider.

For transplant patients, even a 10% drop in drug levels can trigger organ rejection. Many transplant centers have strict policies: no substitutions unless the pharmacy confirms the exact manufacturer and batch. Some providers write “dispense as written” on every prescription for these drugs, blocking automatic substitution by pharmacists.

Why Patients Resist-And How Providers Can Help

It’s not just providers who are cautious. Patients often believe generics are inferior. A 2024 survey in Greece found that 36% of patients thought generic drugs were less effective, even when their doctor recommended them. In the U.S., many patients have received different generic versions of the same drug throughout the year-each with a different pill color, shape, or packaging. They assume each change means a different drug. That confusion leads to anxiety, missed doses, and lower adherence.

But here’s the thing: when providers take just two minutes to explain, patient resistance drops. A study showed that patients who received a simple explanation-“This generic has the same active ingredient, same dose, same effect, just cheaper”-were twice as likely to accept the switch. The key isn’t just telling them. It’s listening. Many patients worry about side effects they’ve read about online. Addressing those fears directly, without judgment, builds trust.

Pharmacists play a critical role too. When a patient picks up a new generic and notices the pill looks different, the pharmacist can say, “This is the same medication, just made by a different company. It’s been approved by the FDA to work exactly the same.” That simple reassurance prevents panic.

State Rules Make It Complicated

Here’s where things get messy: every state has different rules. In 19 states, pharmacists can substitute generics automatically. In 7 states and Washington, D.C., they must get the patient’s consent first. In 24 states, pharmacists face unclear liability rules-if a patient has a bad reaction after a substitution, who’s responsible? That uncertainty makes some pharmacists hesitant to switch, even when it’s allowed.

Thirty-one states require pharmacists to notify patients when a generic is dispensed, even if the patient didn’t ask. But the notice is often buried in fine print on the label. Providers see patients who come in confused, thinking they were given a different drug. It’s not the patient’s fault. It’s the system’s.

Electronic health records (EHRs) are starting to help. Some systems now flag drugs with BX ratings or show therapeutic equivalence codes right in the prescription screen. But not all EHRs are updated. Some still treat all generics as equal. That’s a gap that can lead to unintended substitutions.

Authorized Generics: The Hidden Middle Ground

There’s a version of generics most patients don’t know about: authorized generics. These are the exact same pills as the brand-name drug, just sold without the brand name. For example, the manufacturer of Lipitor might sell its atorvastatin under its own name, but without the Pfizer logo. These are often priced between the brand and regular generics.

Some providers prefer authorized generics because they’re made in the same factory, with the same ingredients and processes as the brand. A 2020 Johns Hopkins study found that patients on authorized generics had outcomes nearly identical to those on the brand-name version. For patients who’ve had bad experiences with regular generics, this can be a trusted middle ground.

But here’s the catch: authorized generics aren’t always available. They’re often discontinued once multiple generic manufacturers enter the market. Providers who want to use them need to check availability each time they prescribe.

The Future: Better Data, Smarter Substitutions

The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative now tracks real-world outcomes for commonly substituted drugs. Instead of relying only on lab tests, they’re watching how patients actually do-hospital visits, ER trips, adherence rates. Machine learning models, like those tested in a 2024 Greek study, are being used to predict which patients are most likely to have issues with substitution. Factors like age, previous reactions, and medication history can help flag high-risk cases.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 is pushing Medicare Part D plans to favor generics even more. By 2025, generic use among seniors could rise another 5-7%. That’s good for the system-but only if providers are prepared. The real challenge isn’t proving generics work. It’s making sure the right ones are used for the right patients.

What Providers Need to Know Now

- Check the Orange Book for therapeutic equivalence ratings before substituting. Look for AB or BX.

- For narrow therapeutic index drugs (warfarin, levothyroxine, immunosuppressants, AEDs), always write “dispense as written” unless the patient and you agree otherwise.

- Use authorized generics when available and when patients have had negative experiences with regular generics.

- Take two minutes to explain the switch. Patients who understand are more likely to stick with the medication.

- Know your state’s substitution laws. Some require consent; others don’t. Liability varies.

- Don’t assume all generics are the same. Different manufacturers can have different fillers or coatings-even if the active ingredient is identical.

Generics aren’t perfect. But they’re not the risky gamble many believe them to be. For most patients, they’re a safe, effective, and affordable choice. The job of the provider isn’t to reject them-it’s to use them wisely.

Are generic medications as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes, for the vast majority of medications, generic drugs are just as effective as their brand-name counterparts. The FDA requires generics to meet strict bioequivalence standards, meaning they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate. Studies involving thousands of patients have shown no meaningful differences in outcomes for drugs like statins, blood pressure medications, and antidepressants. The exception is drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, such as warfarin, levothyroxine, and some antiepileptic drugs, where even small changes can affect outcomes.

Why do some patients have problems after switching to a generic?

Most patients don’t have issues. But some report problems after switching, often due to changes in pill appearance, packaging, or inactive ingredients like fillers and dyes. These changes can cause psychological discomfort or confusion, especially if patients believe they’re getting a different drug. In rare cases, a specific generic version may have manufacturing inconsistencies-like the two versions of Concerta that were downgraded by the FDA in 2016. For patients on narrow therapeutic index drugs, even minor differences in absorption can lead to loss of control over their condition, such as seizures or blood clotting issues.

Can pharmacists substitute generics without my permission?

It depends on your state. In 19 states, pharmacists can substitute a generic without asking. In 7 states and Washington, D.C., they must get your consent first. In 24 states, the rules are unclear, which can lead to inconsistent practices. Always check your prescription label-if a generic was dispensed, the label should say so. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist. You can also ask your provider to write “dispense as written” on your prescription to prevent automatic substitution.

What’s the difference between a generic and an authorized generic?

A regular generic is made by a different company than the brand-name drug, but it contains the same active ingredient. An authorized generic is made by the original brand-name manufacturer and sold under a different label. It’s the exact same pill-same factory, same ingredients, same packaging-just without the brand name. Authorized generics are often more consistent in quality and are a good option for patients who’ve had bad experiences with regular generics, though they’re not always available.

Why do some doctors refuse to prescribe generics?

Most doctors support generics because they’re cost-effective and proven safe. But some avoid them for specific drugs-like antiepileptics, immunosuppressants, or thyroid medications-because of documented cases where substitution led to loss of control over the condition. Others may have had a patient experience a negative outcome after switching. It’s not about distrust of generics overall-it’s about caution with high-risk medications. Many providers use “dispense as written” on prescriptions for these drugs to prevent automatic substitution.

Do generics cause more side effects than brand-name drugs?

No, generics do not cause more side effects than brand-name drugs. The active ingredient is identical, so the potential side effects are the same. However, inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes) can differ between manufacturers, and in rare cases, a patient may have a sensitivity to one of those. That’s why some patients report new side effects after switching-they’re reacting to a different filler, not the medicine itself. If this happens, switching back or trying a different generic often resolves the issue.

How can I tell if my medication is a generic?

Check the prescription label. By law, the pharmacy must list the generic name of the drug, and the packaging will usually say “generic” or list the manufacturer’s name instead of a well-known brand. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist. You can also look up the pill using an online pill identifier-many generics look different from the brand, but they contain the same active ingredient.

Is it safe to switch between different generic manufacturers?

For most medications, yes. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or certain seizure meds-switching between manufacturers can be risky. Even small differences in how the drug is absorbed can affect blood levels. If you’re on one of these medications and your generic changes, talk to your provider. Some patients do best by sticking with the same manufacturer. Your pharmacist can help track which version you’re getting.

Bridget Molokomme

So let me get this straight - we’re paying $150 for a pill that’s chemically identical to the $4 one, and the only difference is the logo? 🤦♀️ I swear, if I had a dollar for every time I was told 'brand name is better' by someone who’s never read the FDA guidelines...

Also, why do pharmacies switch generics every other month? My pill went from blue to green to a weird purple star shape. I thought I was getting a new drug, not a paint sample.