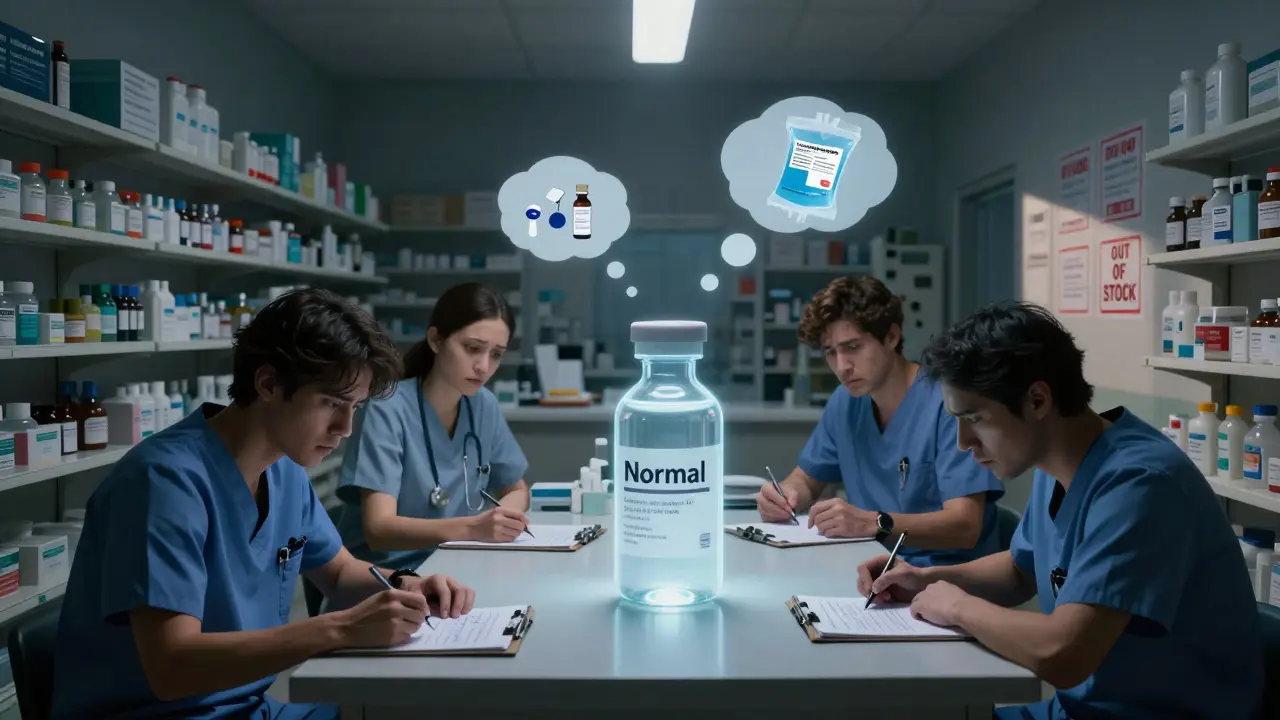

When a patient in the ICU needs a life-saving injection, and the vial isn’t there, it’s not just a logistics problem-it’s a crisis. Hospital pharmacies are the frontline in the fight against injectable medication shortages, and right now, they’re running on empty. While retail pharmacies might see a few missing pills on the shelf, hospitals face entire categories of essential drugs vanishing-drugs that can’t be swapped out for a pill or a liquid. These aren’t convenience issues. They’re survival issues.

Why Injectables Are the First to Go

Not all drugs are created equal when it comes to supply chains. Injectable medications-especially sterile ones-require clean rooms, precise mixing, and strict quality controls. A single speck of dust can ruin a batch. That’s why manufacturing them is expensive, slow, and risky. And because they’re mostly generic, profit margins are razor-thin. Most manufacturers operate on 3-5% margins. When a machine breaks, a power outage hits, or the FDA flags a facility for contamination, there’s little financial incentive to fix it fast-or at all. The numbers don’t lie. As of July 2025, 226 drugs were in shortage across the U.S., and nearly 60% of them were injectables. That’s up from just 15% a decade ago. Anesthetics? 87% in shortage. Chemotherapy drugs? 76%. Cardiovascular injectables? 68%. These aren’t obscure medications. They’re the backbone of emergency care, surgery, cancer treatment, and ICU management.The Supply Chain Is a Single Point of Failure

Here’s the scary part: 80% of the active ingredients for generic injectables come from just two countries-China and India. One tornado in North Carolina, like the one that hit Pfizer’s plant in October 2023, can knock out 15 critical drugs at once. A quality failure at a facility in India in early 2024 shut down cisplatin production nationwide, a drug used to treat lung, ovarian, and testicular cancers. No one was prepared. No backup existed. And it’s not just natural disasters or foreign policy. Manufacturing quality issues cause 55% of all drug shortages, according to FDA data. A single failed inspection can halt production for months. Even worse, the market is now dominated by just three manufacturers for key drugs like normal saline and potassium chloride. That means if one fails, the entire country feels it.Hospital Pharmacies Are Hit Twice as Hard

Retail pharmacies manage shortages affecting about 15-20% of their inventory. Hospital pharmacies? 35-40%. And 60-65% of those are sterile injectables. Why? Because hospitals don’t just treat colds or migraines. They treat heart attacks, sepsis, trauma, and cancer. These patients need drugs delivered directly into the bloodstream. Oral alternatives don’t work. Topical creams won’t cut it. And substitutions? They’re risky. Take normal saline. It’s used in nearly every hospital procedure-from IV hydration to flushing catheters to diluting other drugs. When it disappeared in late 2024, hospitals scrambled. Some switched to oral rehydration for post-op patients. Others postponed surgeries. One nurse manager in Massachusetts documented 37 canceled procedures in just three months because they couldn’t get enough saline. Academic medical centers report being hit 2.3 times harder than community hospitals. Why? They handle the sickest patients-the ones who need the most specialized injectables. When anesthetic supplies run low, surgeries get delayed. When chemo drugs vanish, treatment schedules collapse. And when patients are waiting, time isn’t just money-it’s life.

What Happens When the Drugs Run Out

It’s not just about delays. It’s about compromise. A 2025 survey by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists found that 68% of hospital pharmacists have faced ethical dilemmas during shortages. Forty-two percent admitted they’ve had to use less effective alternatives that could harm outcomes. One pharmacist on Reddit shared how they were forced to use oral fluids for post-op patients-something they’d never done before. "Never thought I’d see the day," they wrote. Hospital staff are burning out. Pharmacists spend an average of 11.7 hours a week just tracking down drugs, calling suppliers, and approving substitutions. Nurses are being asked to stretch doses, split vials, or use expired stock. The stress is real. And the mistakes? They’re rising. Only 45% of hospitals have formal, updated shortage protocols. Thirty-one percent are still using ad-hoc, handwritten lists. That’s how errors happen. That’s how patients get hurt.Why Fixes Keep Failing

The government has tried. The FDA’s Drug Supply Chain Security Act requires better tracking. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 demanded earlier shortage notifications. But a 2025 GAO report showed those changes only reduced shortage duration by 7%. The FDA can’t force manufacturers to produce more. It can’t punish them for letting a facility sit idle. It can’t fix the low-profit model that makes these drugs unattractive to invest in. The Biden administration pledged $1.2 billion in 2024 to boost domestic production. But experts say it’ll take 3-5 years to see results. Meanwhile, only 12% of sterile injectable makers have adopted newer technologies like continuous manufacturing-systems that could make production faster and more resilient. Most still rely on decades-old equipment. The FDA’s 2025 Strategic Plan for Drug Shortage Prevention sounds good on paper. But without enforcement, it’s just a wishlist. The American Medical Association called it "insufficient to address the systemic nature of the problem." And they’re right.

What Hospitals Are Doing to Cope

They’re getting creative. Some hospitals have formed shortage management teams-dedicated staff who monitor inventory, approve substitutions, and coordinate with other facilities. But only 32% of these teams feel properly funded or staffed. Others are building direct relationships with smaller, regional suppliers. A few are stockpiling critical drugs when they can-though storage limits and expiration dates make that risky. Therapeutic interchange protocols are now standard. That means pharmacists and doctors work together to find the closest safe alternative. But it takes time. It takes training. And it takes paperwork. One University of Michigan study found new pharmacy directors need an average of 6.2 months to get good at managing shortages. The best-run hospitals have consolidated their stock-keeping all scarce drugs in one central location to reduce waste and improve tracking. They’ve revised standing orders to include approved alternatives. They’ve trained nurses on how to spot signs of a shortage before it hits. But none of this solves the root problem.The Road Ahead

The number of active shortages dropped from 270 in April 2025 to 226 by July. That sounds like progress. But 89% of the shortages in 2024 carried over from 2023. That means the same drugs, the same problems, the same hospitals struggling. Without major changes-higher reimbursement for generic injectables, incentives for modern manufacturing, penalties for chronic underproduction, and true supply chain diversification-this won’t get better. It’ll get worse. Climate change is bringing more storms. Geopolitical tensions are making global supply chains more fragile. And as the population ages, demand for these drugs will only climb. The elderly-65 to 85 years old-make up over 30% of those affected by shortages. They’re the ones in hospital beds. They’re the ones waiting. Hospital pharmacies aren’t failing. They’re holding the line. But they can’t do it alone. The system is broken. And if we don’t fix it soon, the next shortage won’t just delay treatment. It could cost a life.Why are injectable medications more likely to be in shortage than pills?

Injectable medications require sterile manufacturing environments, complex quality controls, and precise formulations. They’re harder and more expensive to produce than pills. Plus, most are generic, so manufacturers make very little profit-often just 3-5%. That means companies don’t invest in backup equipment or multiple production sites. One machine failure or FDA inspection can shut down supply for months.

Which drugs are most commonly in shortage right now?

As of mid-2025, the most affected categories are anesthetics (87% shortage rate), chemotherapy drugs like cisplatin and doxorubicin (76%), and cardiovascular injectables like epinephrine and nitroglycerin (68%). Common fluids like normal saline and potassium chloride have also faced critical shortages due to manufacturing concentration and supply chain fragility.

How do shortages affect patients?

Shortages lead to delayed surgeries, postponed cancer treatments, and substituted medications that may be less effective or carry higher risks. Over 78% of hospital pharmacists report treatment delays for critically ill patients in the past year. In some cases, patients have been sent home with oral fluids instead of IV hydration, or received lower-dose chemo regimens because the full dose isn’t available.

Can hospitals just order more from another country?

Not easily. Most generic injectables come from just two countries-China and India-and the FDA must approve every batch. Even if a hospital finds a foreign supplier, the drug must meet U.S. standards, which can take months to verify. Plus, many foreign facilities have been shut down by the FDA for quality issues. There’s no quick global backup.

Is there any hope for improvement?

Yes-but only with systemic change. The $1.2 billion federal investment in domestic manufacturing could help, but it will take 3-5 years to show results. Long-term solutions include raising reimbursement rates for generic injectables, incentivizing modern manufacturing tech like continuous production, and requiring manufacturers to maintain backup production lines. Without these, shortages will keep coming, and hospitals will keep struggling.

Andy Heinlein

Man, i’ve seen this play out in my hospital. One day we’re fine, next day no saline, no epinephrine, no damn potassium. Nurses are splitting vials like it’s a damn science fair project. We’re not superheroes, y’know? Just people trying not to kill folks with bad math.

And yeah, the gov’s throwing money at it, but it’s like putting bandaids on a dam. The real fix? Pay manufacturers more to make boring, life-saving junk. Not sure why that’s so hard to get.