When you pick up a prescription, you probably don’t think about the dozens of companies racing to make the same drug cheaper. But behind every pill, there’s a battle - one that shapes how much you pay. The key player in that battle isn’t the doctor or the pharmacy. It’s generic drug competition.

Why generics change everything

Generic drugs aren’t knockoffs. They’re identical copies of brand-name medicines, approved by the FDA after proving they work the same way, in the same dose, and with the same safety profile. The difference? Price. A brand-name drug might cost $500 for a 30-day supply. Once a few generics hit the market, that same pill drops to $10. With six or more generic makers, it often falls below $5. Studies show that when nine generic versions are available, prices drop by 97.3% on average. This isn’t magic. It’s basic economics: more sellers = lower prices. But in pharma, it’s not automatic. Brand companies fight hard to delay generics - through patent tricks, lawsuits, and even paying generic makers to stay off the market. These so-called "reverse payments" delayed entry for over 100 drugs between 2010 and 2020, according to the FTC. That’s why buyers - governments, insurers, pharmacy benefit managers - don’t just wait. They actively use competition as leverage.How payers turn competition into negotiating power

Buyers don’t just accept whatever price a company sets. They use the threat - or reality - of generic alternatives to force lower prices. In the U.S., Medicare now has legal authority to directly negotiate prices for certain high-cost drugs under the Inflation Reduction Act. But here’s the twist: they can’t negotiate with a drug that already has generic versions. So instead, they use those generics as a benchmark. CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) looks at the average price of all similar drugs on the market - brand and generic - and sets a starting point for negotiations. If a brand-name drug costs $300 and there are three generics selling for $8 each, CMS doesn’t start at $300. It starts near the generic price range. Then it adjusts based on clinical data. The goal? Make sure the brand doesn’t charge more than it needs to, knowing generics are already undercutting it. Other systems do this even more directly. Canada’s tiered pricing model lowers the maximum allowable price every time a new generic enters the market. More competitors? Lower ceiling. Simple. Predictable. And it works: Canada spends far less per drug than the U.S., even though it has the same innovation.

The hidden cost of delaying competition

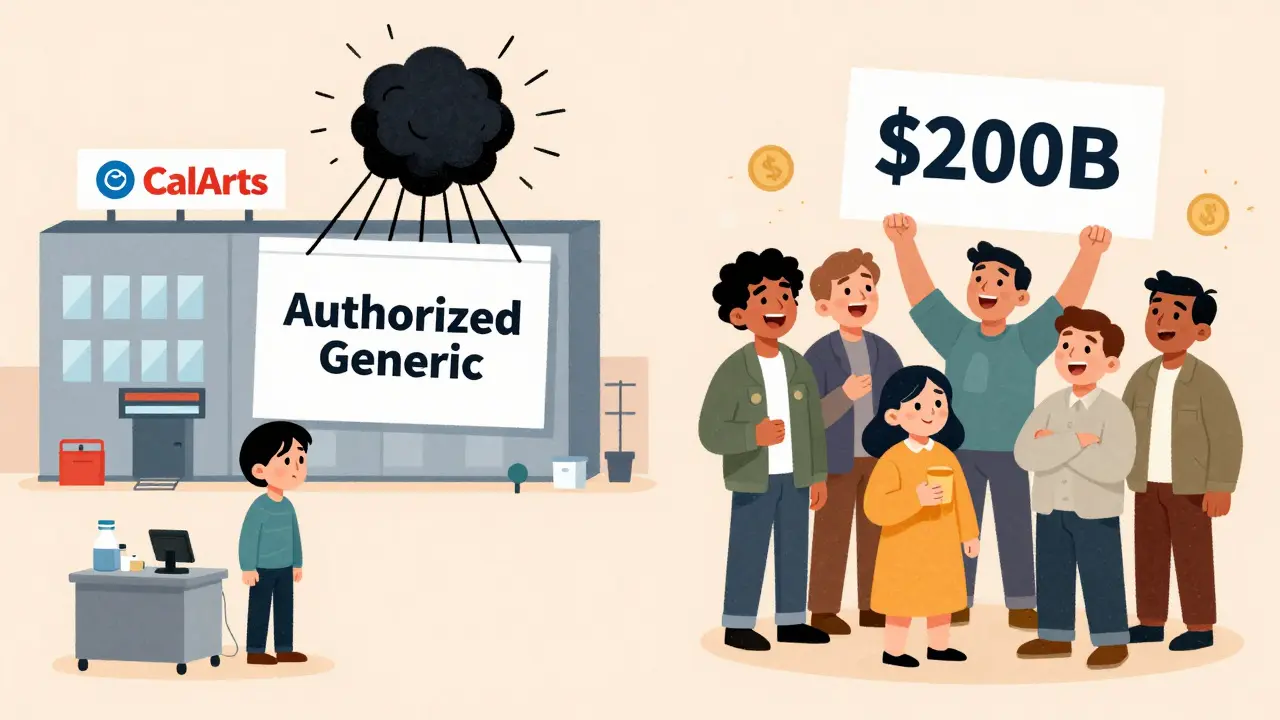

Brand companies don’t sit still. They use "product hopping" - making tiny changes to a drug (like switching from a pill to a capsule) just before generics launch - to reset the patent clock. Between 2015 and 2020, there were 1,247 of these maneuvers, according to FTC data. Each one delays cheaper options by months or years. And then there’s the "authorized generic" trick. A brand company will launch its own generic version - often at a slightly lower price than independent generics - to scare off competitors. It looks like competition, but it’s really a way to control the market and keep profits high. Independent generic makers say this makes entry too risky. Why invest millions to build a factory if the brand will undercut you the moment you launch? This isn’t theoretical. Avalere Health found that when the government sets a low price for a brand drug before generics arrive, it kills the incentive for generics to even try. Why risk $10 million in legal fees and manufacturing costs if you can’t make back your investment? That’s the "chilling effect" - and it’s real.Who wins and who loses

Patients win when generics flood the market. In the U.S., 90% of prescriptions are filled with generics, but they make up only 22% of total drug spending. That’s a $200 billion annual savings, according to IQVIA. For Medicare beneficiaries, the first 10 drugs negotiated under the Inflation Reduction Act could save $6.8 billion per year. But the system isn’t perfect. Small generic manufacturers - the ones with limited resources - struggle the most. They need predictable pricing to justify investing in new facilities or complex drugs. A 2022 survey by the European Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Association found that 78% of generic makers say pricing stability is essential to enter a market. When rules change fast - like when CMS suddenly sets a low price for a brand drug - they pull back. Meanwhile, big generic players like Teva, Sandoz, and Viatris dominate. Together, they control 35% of the global market. That’s not competition. It’s consolidation. And it’s a problem. When only a few companies make a drug, price drops stall. That’s why regulators now watch for market concentration as much as patent delays.

What’s next for drug pricing

The next big shift is in complex drugs - biosimilars, injectables, and specialty generics. These aren’t like your everyday pill. They’re harder to copy, cost more to make, and take years to get approved. Right now, biosimilars have only a 45% market share, compared to 90% for simple generics. That’s because manufacturers are scared: the market is small, the costs are high, and the rules are unclear. Some new ideas are emerging. The proposed EPIC Act would delay Medicare price negotiations until after generics have had a fair chance to enter. That way, the market gets to work first - letting competition do its job - before the government steps in. It’s a compromise: let generics fight, then use their prices as a floor for negotiations. Other countries are moving faster. The UK updated its pricing system in 2023 to use prices from other European nations as a reference. Germany and Japan are experimenting with real-world data - using actual patient outcomes to set prices, not just lab results.What this means for you

If you’re on a long-term medication, ask your pharmacist: "Is there a generic?" If yes, and it’s not being offered, ask why. Sometimes, it’s just a formulary issue - your insurer hasn’t updated its list. Other times, the brand company is using tricks to block it. If you’re paying out of pocket, check GoodRx or Blink Health. They show you the lowest cash price - often from a generic maker - even if your insurance doesn’t cover it. You’d be surprised how often the cash price is lower than your copay. And if you’re part of a health system or employer group negotiating drug prices? Don’t just look at the brand. Look at the generics. Count them. Track their prices. Use that data as your hammer. Because in drug pricing, competition isn’t just a nice idea - it’s the most powerful tool we have.How do generic drugs lower prices so dramatically?

When multiple generic manufacturers produce the same drug, they compete on price. The first few generics might drop the price by 50-70%. With six or more competitors, prices often fall by over 90%. This happens because generic makers don’t need to recoup billions in R&D costs like brand companies do. Their only goal is to produce the drug cheaply and sell it in volume.

Why doesn’t Medicare negotiate with drugs that already have generics?

The Inflation Reduction Act prohibits direct negotiation for drugs with existing generic competition because the market is already driving prices down. Instead, Medicare uses the prices of those generics as a benchmark to set lower starting prices for brand-name drugs - effectively using competition as leverage without directly interfering in a functioning market.

Can I ask my doctor to prescribe a generic drug?

Yes - and you should. Most brand-name drugs have FDA-approved generic versions that are just as safe and effective. Ask your doctor to prescribe the generic unless there’s a specific medical reason not to. Even if your insurance covers the brand, the generic might cost you less out-of-pocket.

What are "authorized generics" and why do they matter?

An authorized generic is a version of a brand-name drug sold under a different label, often by the same company. It’s not a true competitor - it’s a tactic to undercut independent generic makers. When a brand launches its own generic, it can scare off other companies from entering the market, reducing competition and slowing price drops.

Why do some drugs still cost so much even with generics available?

Sometimes, only one or two generic makers enter the market - either because the drug is hard to produce, or because the brand company blocked others with legal tactics. Other times, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) don’t push for the cheapest option. If there’s little competition, prices stay high. Always check multiple sources like GoodRx to find the lowest cash price.

Are generic drugs as safe and effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand. They must also prove they’re absorbed in the body at the same rate and to the same extent. Over 90% of U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics, and studies show no difference in effectiveness or safety.

Jane Wei

bro i just checked my last script and it was $4 with goodrx. same pill my buddy paid $380 for last year. wild how this stuff works when no one’s watching.