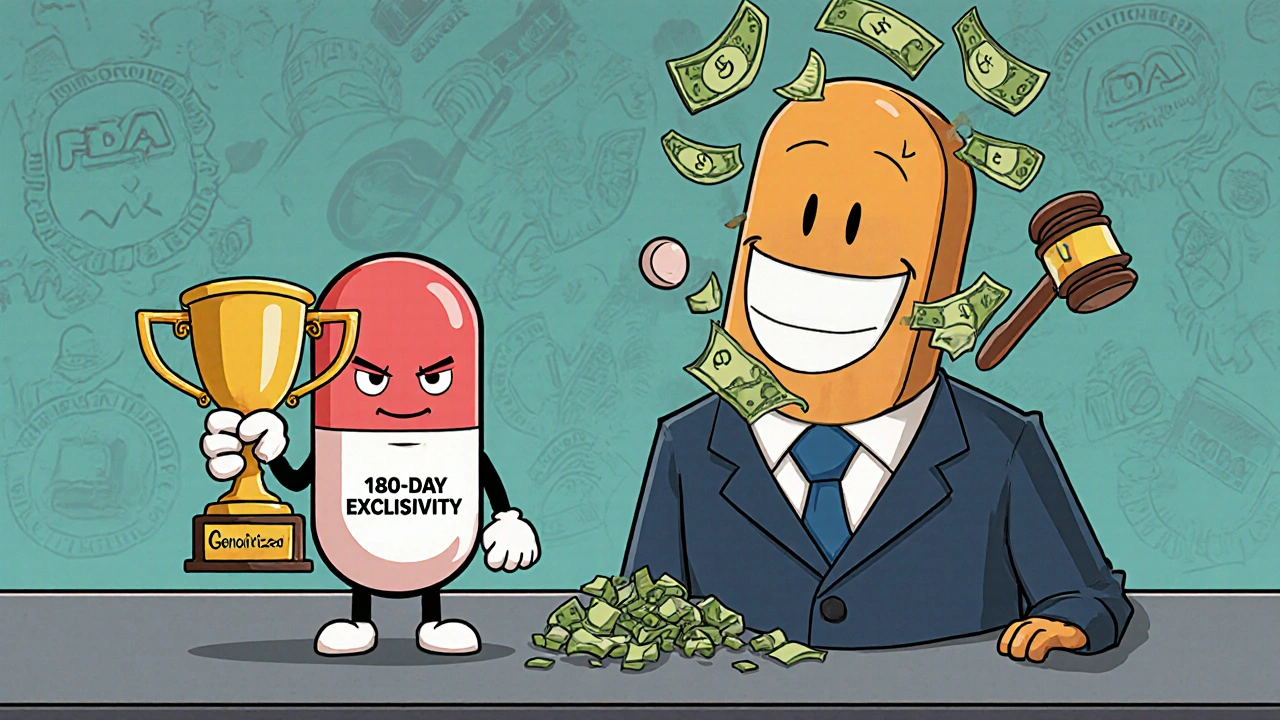

When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, the first generic company to challenge that patent gets a powerful reward: 180 days of exclusive rights to sell the generic version. This isn’t just a perk-it’s a financial lifeline. In some cases, that window can mean hundreds of millions in revenue. But here’s the catch: the brand-name company can still launch its own version of the generic drug during that same 180-day period. It’s the same pill, same factory, same formula-but without the brand name. This is called an authorized generic, and it’s legal. And it’s wrecking the incentive the law was meant to create.

How the 180-Day Clock Starts

The 180-day exclusivity rule comes from the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. It was designed to get cheaper drugs to patients faster by giving generic makers a reason to fight expensive patent lawsuits. To qualify, a generic company must file what’s called a Paragraph IV certification. That’s a formal legal challenge saying the brand’s patent is invalid or won’t be infringed. If they win in court-or if the brand settles-the clock starts ticking. The 180 days begin when the generic company actually starts selling the drug, not when it gets FDA approval. This detail matters. If you ship the product too early, before approval is final, you risk losing your exclusivity. If you wait too long, someone else might beat you to market.The FDA’s 2017 guidance makes this clear: commercial marketing means more than just getting paperwork signed. You need to have the product in the hands of distributors or pharmacies. One generic manufacturer lost 45 days of exclusivity in 2020 because they shipped the drug before the FDA’s final approval notice arrived. That’s $12 million in lost revenue, according to internal company documents cited in a 2021 industry report.

What Is an Authorized Generic?

An authorized generic isn’t a copy. It’s the real thing. The brand-name company partners with a generic manufacturer to produce and sell the exact same drug under a different label. No bioequivalence studies. No new FDA application. Just a new box, a lower price, and the same active ingredients. It’s like Coca-Cola selling its own store-brand cola under a white label. The FDA doesn’t treat it as a competitor-it treats it as the original drug.Between 2005 and 2015, brand-name companies launched authorized generics in 60% of cases where 180-day exclusivity was granted. That’s not coincidence. It’s strategy. When the first generic hits the market, the brand-name company hits back with its own version. Suddenly, instead of one generic taking 80% of the market, you’ve got two products that are identical in every way except the label. The result? The first generic’s market share drops to about 50%. Revenue plummets by 30% to 50%.

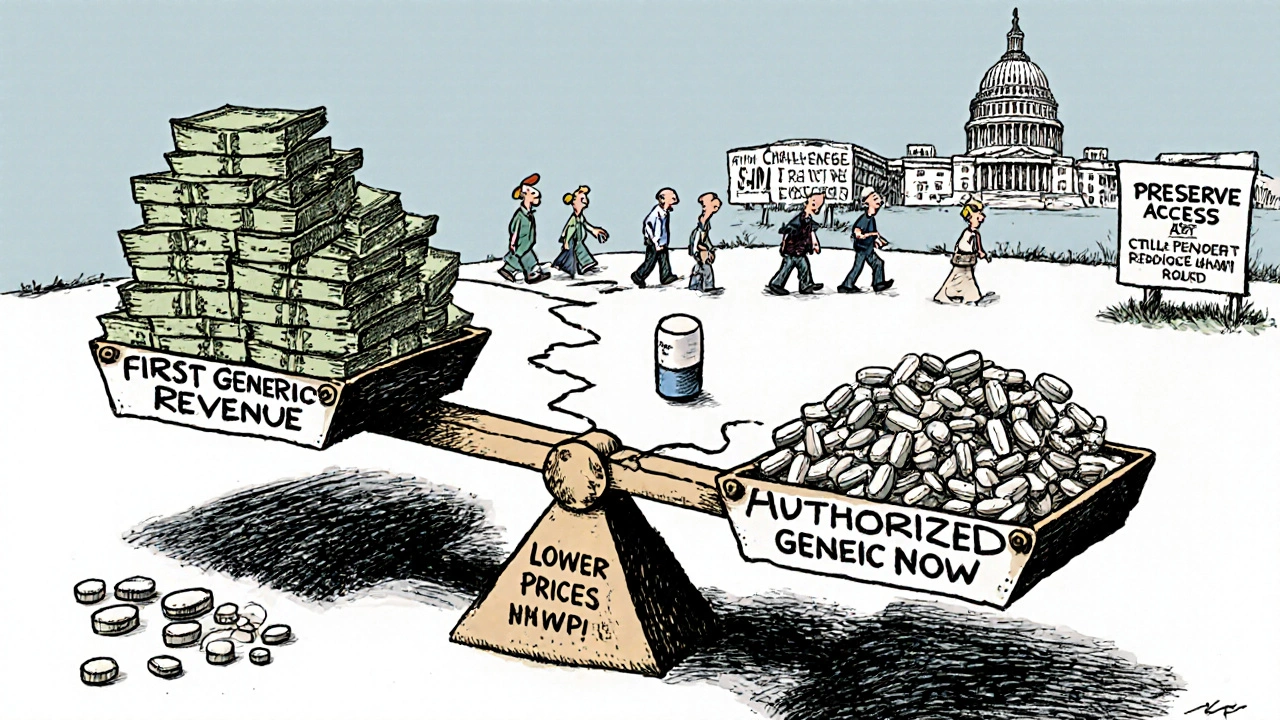

Why This Breaks the System

The whole point of the 180-day exclusivity is to reward risk. Challenging a patent costs $2 million to $5 million in legal fees. It takes years. Smaller generic companies often go bankrupt trying. The promise of a monopoly for half a year was supposed to make that risk worth it. But when the brand-name company enters the market with an authorized generic, it’s like giving the same prize to two people. The first one still gets the trophy-but now the second one is selling the same thing for the same price, right next to them.Television’s biggest drama? No. This is real. In 2019, Teva Pharmaceuticals sued Eli Lilly after Lilly launched an authorized generic of Humalog, a diabetes drug Teva had spent $150 million and five years challenging in court. Teva estimated it lost $287 million in revenue because of it. That’s not an outlier. Evaluate Pharma found that between 2015 and 2020, the average first generic company captured just 52% of the revenue it expected during its exclusivity window. The rest went to the brand’s own version.

Legal Loopholes and Settlement Deals

You’d think the courts would step in. But they don’t. The law doesn’t ban authorized generics. So companies have turned to private deals. Drug Patent Watch found that 78% of first generic applicants now negotiate contracts with brand-name companies to delay or block authorized generic launches. These are called “reverse payment settlements.” The brand pays the generic to stay out of the market-or to not launch an authorized version. The FTC calls this anti-competitive. Courts have called it legally gray.In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in Actavis v. FTC that these payments could violate antitrust laws-if they’re large enough and lack a legitimate business reason. But proving that in court is hard. Most settlements are sealed. Most generic companies are too small to fight. And the brand-name companies? They’ve got armies of lawyers. In 2022, the FTC filed its 15th antitrust lawsuit against a pharmaceutical company for using authorized generics to delay competition. So far, none have resulted in a ban on the practice.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

Consumers often think more competition means lower prices. And in theory, that’s true. A 2021 RAND Corporation study showed that when an authorized generic competes with a first generic, prices drop 15% to 25% faster than if only one generic is on the market. That’s good for patients paying out of pocket.But here’s the flip side: the first generic company gets crushed. If they can’t make money on their exclusivity period, they won’t challenge the next patent. And if they don’t challenge, the brand keeps its monopoly longer. That’s bad for patients in the long run. The Generic Pharmaceutical Association says the Hatch-Waxman Act has saved the U.S. healthcare system $2.2 trillion since 1984. But that number is shrinking. In 2000, it took an average of 28 months for multiple generics to enter the market after patent expiry. In 2022, it took just nine months. Why? Because authorized generics flood the market immediately, killing the incentive for others to come in.

What’s Changing?

Congress has tried to fix this. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act has been introduced in every session since 2009. It would ban brand-name companies from launching authorized generics during the 180-day window. FDA Commissioner Robert Califf told Congress in March 2023 that the agency supports this change. The FTC agrees. They estimate that banning authorized generics during exclusivity would boost first generic revenues by 35% on average.But the pharmaceutical industry pushes back. PhRMA argues that authorized generics are good for patients. They say the FDA’s own data shows prices are lower when authorized generics are present. And they’re not wrong. But the question isn’t just about price. It’s about sustainability. If the only way to make a profit is to cut a deal with the brand, then the system isn’t working. It’s just been gamed.

Smaller generic manufacturers are already leaving the game. Reddit threads from pharmaceutical professionals in early 2023 show a pattern: “Why risk $4 million in legal fees if the brand can just slap their own version on the shelf?” One company owner in Ohio told a reporter he’d stopped filing Paragraph IV certifications entirely. “We’re not a hedge fund,” he said. “We’re a pharmacy. We need to survive.”

The Future of Generic Competition

The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to balance innovation and access. But after 40 years, the scales are tilted. The 180-day exclusivity was supposed to be the engine of generic competition. Now, it’s a trap. The first company to challenge a patent gets a prize-but only if the brand lets them keep it.Until Congress acts, the only way for generic companies to protect themselves is through legal contracts, expensive consulting, and perfectly timed launches. Large firms like Teva and Mylan have teams of regulatory, legal, and commercial experts working months in advance just to preserve a few weeks of exclusivity. Smaller companies? They’re outgunned.

The real winners? Patients who get cheaper drugs now. The real losers? The next generation of generic manufacturers who won’t have the resources-or the incentive-to challenge the next patent. And eventually, that means fewer generics. Slower access. Higher prices. The system was built to prevent that. But it’s failing.

What triggers the 180-day exclusivity period for a generic drug?

The 180-day exclusivity period begins when the first generic applicant starts commercial marketing of the drug-meaning the product is shipped to distributors or pharmacies after receiving FDA approval. Simply getting approval isn’t enough. The FDA requires actual sales activity to trigger the clock. Premature shipping before final approval can forfeit the exclusivity.

Can a brand-name company sell its own drug as a generic during the 180-day exclusivity period?

Yes. This is called an authorized generic. It’s the exact same drug, made in the same facility, with the same active ingredients, just sold under a different label. The FDA allows this because it doesn’t consider it a new drug application. This practice is legal and has been used in 60% of cases where 180-day exclusivity was granted between 2005 and 2015.

Why do generic companies still challenge patents if authorized generics can undercut them?

Many do it anyway because the financial upside can still be huge-if the brand doesn’t launch an authorized generic. In those cases, the first generic can capture up to 80% of the market. Also, many generic companies now negotiate settlements with brand-name manufacturers to block authorized generic entry. About 78% of first applicants include these clauses in their patent litigation deals.

What’s the difference between an authorized generic and a regular generic?

A regular generic is made by a different company and must prove bioequivalence to the brand-name drug through FDA testing. An authorized generic is made by the brand-name company or under contract with them, using the same formula and manufacturing process. It doesn’t need FDA approval as a new product-it’s just relabeled. The only difference is the packaging and price.

Is there legislation to stop authorized generics during the 180-day period?

Yes. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act has been reintroduced in Congress multiple times since 2009. It would prohibit brand-name manufacturers from launching authorized generics during the 180-day exclusivity window. The FDA and FTC support this change, arguing it would restore the original intent of the Hatch-Waxman Act. But the bill has not passed due to opposition from pharmaceutical industry groups.

How do authorized generics affect drug prices?

Authorized generics lower prices faster in the short term. A 2021 RAND Corporation study found that when an authorized generic competes with the first generic, prices drop 15% to 25% more quickly than if only one generic is on the market. But in the long term, they discourage future generic competition by reducing the financial reward for patent challenges, which can delay broader generic entry and lead to higher prices later.

What Generic Manufacturers Should Do Now

If you’re a generic company preparing a Paragraph IV challenge, don’t assume exclusivity is guaranteed. Build your strategy around the threat of an authorized generic. Negotiate settlement terms that include a commitment from the brand not to launch an authorized version. Budget for the possibility that your market share will be cut in half. Invest in regulatory and legal teams early. And if you’re a small company, think twice before spending $4 million on a patent fight if the brand has a history of launching authorized generics.The law gave you a tool. But the brand-name companies found a way to turn it into a trap. The system still works-if you know how to play it. But the game has changed. And if you don’t adapt, you won’t survive.

Ginger Henderson

Honestly? This whole system is just a joke.