When you take opioids for chronic pain, you might not think about your breathing while you sleep. But for many people, that’s exactly where the danger lies. Opioids don’t just dull pain-they slow down your breathing, especially at night. And if you already have sleep apnea, this combination can be deadly.

What Happens When Opioids Meet Sleep Apnea?

Sleep apnea means your breathing stops and starts repeatedly during sleep. There are two main types: obstructive (when your throat muscles relax and block your airway) and central (when your brain doesn’t send the right signals to breathe). Opioids make both worse.These drugs act on brainstem areas that control breathing, like the pre-Bötzinger complex. The result? Your body becomes less responsive to low oxygen and high carbon dioxide levels. Studies show opioids can reduce your hypoxic ventilatory response by 25-50% and your hypercapnic response by 30-60%. In plain terms: your body stops checking if you’re getting enough air.

At the same time, opioids relax the muscles in your upper airway-especially the genioglossus muscle that keeps your tongue from blocking your throat. This drops the pressure needed to keep your airway open by 2-4 cm H₂O. That’s enough to turn a mild snorer into someone who stops breathing dozens of times a night.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

One in five adults in the U.S. takes prescription opioids each year. And nearly three-quarters of those on long-term therapy have moderate to severe sleep apnea. That’s not coincidence-it’s cause and effect.

People using opioids have an average apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 25-35 events per hour. That’s considered severe. Compare that to non-users with similar body weight, who average 15-20. Even more alarming: central sleep apnea (CSA) is 3-5 times more common in opioid users. One study found 80% of chronic opioid users had CSA with a mean central apnea index of 12.3 events per hour.

Nighttime oxygen levels crash harder, too. In one study, 68% of opioid users had oxygen saturation below 88% for more than five minutes during sleep. Only 22% of non-users did. And when someone already has untreated obstructive sleep apnea, adding opioids raises their risk of oxygen dropping below 80% by 3.7 times.

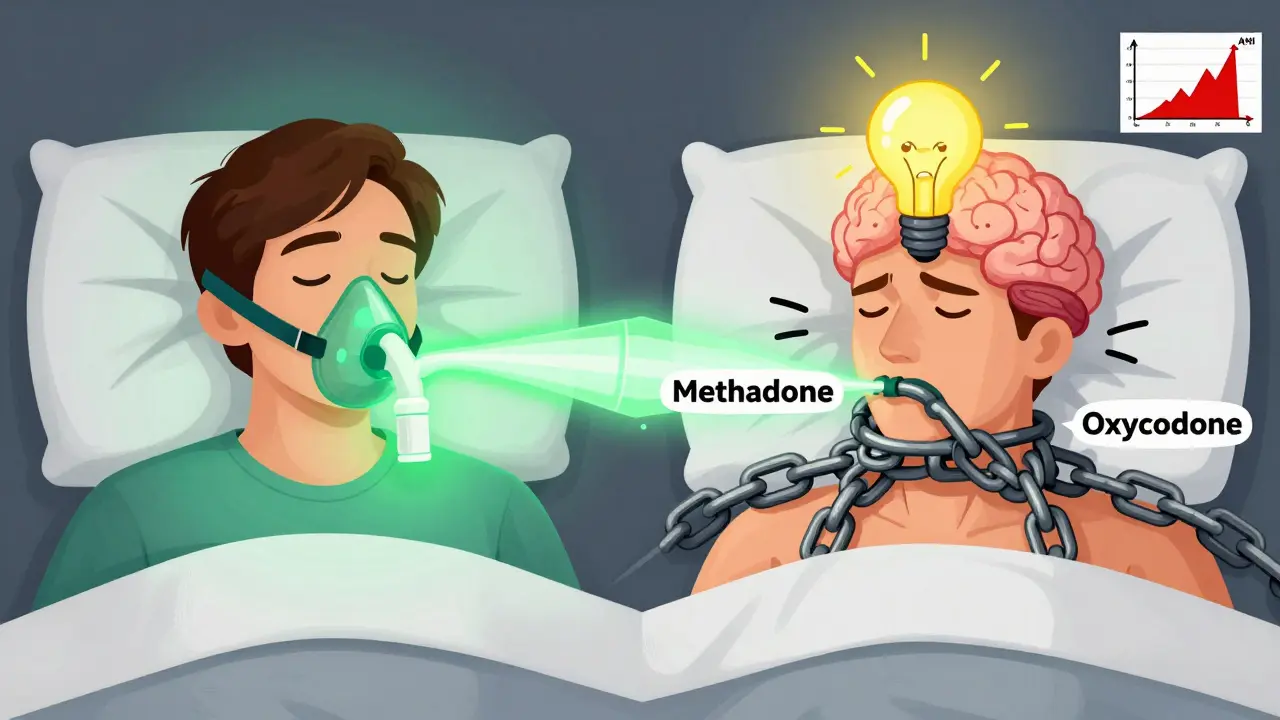

Methadone is the worst offender. Doses over 100 mg per day are linked to central apnea indexes above 20 in 65% of users. Even a 10 mg increase in morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) raises AHI by 5.3%. That’s why experts say: if you’re on more than 50 MEDD, you’re in the danger zone.

Why This Is a Silent Killer

Most people don’t realize they’re at risk because the symptoms sneak up slowly. You might think you’re just tired from pain or aging. But waking up gasping for air, dry mouth in the morning, or being told you stop breathing while sleeping? Those aren’t normal.

The real danger? It happens when you’re asleep-no one’s there to help. Respiratory arrest during sleep is silent. No screams. No flailing. Just a slow drop in oxygen that can lead to cardiac arrest, stroke, or death.

One study found that patients with both untreated sleep apnea and opioid use had double the risk of death compared to those with either condition alone. Dr. Kingman P. Strohl from Case Western Reserve put it bluntly: “Opioids and sleep apnea represent a perfect storm for respiratory compromise during sleep.”

Who’s Most at Risk?

You’re at higher risk if you:

- Take opioids daily for more than three months

- Use doses over 50 MEDD (morphine equivalent daily dose)

- Have obesity (BMI ≥30)

- Snore loudly or have been told you stop breathing at night

- Have been diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea before

- Use methadone or high-dose oxycodone

Even if you don’t fit all these, don’t assume you’re safe. One patient in a 2022 case series had no history of snoring or obesity-but still had severe central apnea on 60 mg of oxycodone daily.

What Should You Do?

If you’re on long-term opioids, don’t wait for symptoms. Get tested.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine now recommends polysomnography (a full overnight sleep study) for anyone starting long-term opioid therapy at doses above 50 MEDD-especially if you’re overweight or snore. But most doctors don’t do this. A 2021 survey found only 28% of primary care physicians routinely screen for sleep apnea before prescribing opioids.

Here’s what you can do:

- Ask your doctor: “Could my opioids be affecting my breathing at night?”

- If you snore, feel tired during the day, or wake up gasping, insist on a sleep study.

- Ask about home sleep apnea testing (HSAT). The FDA cleared the Nox T3 Pro in January 2023 specifically for opioid users-it’s accurate, convenient, and covered by most insurance.

Once diagnosed, treatment works. CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) is the gold standard for obstructive sleep apnea. But adherence is low in opioid users-only 58% stick with it, compared to 72% in non-users. Why? Opioids cause brain fog and fatigue, making the mask feel more uncomfortable.

Alternative options include:

- Lowering your opioid dose (if possible, under medical supervision)

- Switching to a less respiratory-depressant opioid like buprenorphine

- Positional therapy (sleeping on your side)

- Acetazolamide, a drug being tested in clinical trials that reduced AHI by 35% in early results

The Bigger Picture

Over 10 million Americans are on long-term opioid therapy. That’s more than the population of New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago combined. And we’re only just beginning to understand how many of them are silently suffocating at night.

Some researchers are now looking at genetics. The NIH’s Opioid Sleep Apnea Registry is tracking 1,200 patients to find genetic markers that predict who’s most vulnerable. Early results show people with certain PHOX2B gene variants have over three times the risk of severe central apnea on opioids.

Meanwhile, drug companies are testing new painkillers like cebranopadol that might relieve pain without crushing breathing. But those are years away. Right now, the solution is simple: screen, diagnose, treat.

At the Cleveland Clinic, implementing routine sleep apnea screening for opioid patients cut respiratory events by 41% in just 18 months. At the University of Michigan, 78% of patients referred for sleep evaluation had undiagnosed apnea. Many were shocked-but saved.

What Patients Are Saying

On Reddit’s r/ChronicPain, users share real stories:

- “I started oxycodone and woke up every night choking. I thought I was dying. My sleep study showed severe apnea. CPAP changed my life.”

- “My doctor said my fatigue was from pain. I asked for a sleep test. Turns out I had central apnea. They lowered my dose and added oxygen at night. I haven’t felt this awake in years.”

- “I quit opioids and my apnea didn’t improve. My brain had forgotten how to breathe on its own.”

These aren’t outliers. They’re warning signs we’re ignoring.

Final Warning

Opioids are powerful tools for pain-but they’re not harmless. If you’re on them long-term, your breathing during sleep is at risk. Nighttime hypoxia doesn’t come with a buzzer or alarm. It creeps in quietly, and by the time you feel it, it might be too late.

Don’t wait for a near-death experience. If you take opioids, ask for a sleep study. If your doctor says no, ask again. Or find someone who will listen.

Your life depends on it.

Can opioids cause central sleep apnea even if I don’t have obstructive sleep apnea?

Yes. Opioids directly suppress the brain’s breathing control centers, leading to central sleep apnea-where the brain stops sending signals to breathe-even in people who’ve never had snoring or airway blockage. Studies show 80% of chronic opioid users develop central apnea, with an average of 12 central events per hour, regardless of body weight or prior sleep history.

Is it safe to take opioids if I already have sleep apnea and use CPAP?

It’s risky, but manageable. CPAP helps with obstructive events, but opioids still cause central apnea and blunt your body’s natural response to low oxygen. Many patients on both opioids and CPAP still experience nighttime oxygen drops. Your doctor should monitor your oxygen levels during sleep and consider lowering your opioid dose or switching medications. Never assume CPAP makes you completely safe.

What opioid dose is considered dangerous for sleep apnea?

Doses above 50 morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) significantly increase risk. At 100 MEDD or higher, over 65% of users develop severe central sleep apnea. Even 20-30 MEDD can worsen existing apnea. There’s no “safe” dose-only lower risk. The CDC recommends screening for sleep apnea before starting opioids at any dose, but especially above 50 MEDD.

Can I stop opioids to fix my sleep apnea?

Sometimes, but not always. For many, stopping opioids improves breathing within weeks. But in some cases-especially after years of high-dose use-the brain’s breathing control may be permanently altered. One case report showed no improvement in apnea after opioid discontinuation, suggesting neural adaptation. Never quit opioids abruptly-work with your doctor on a taper plan while monitoring your sleep.

Are there alternatives to CPAP for opioid-induced sleep apnea?

Yes. For central apnea, acetazolamide (a diuretic that stimulates breathing) has shown a 35% reduction in apnea events in early trials. Positional therapy, oxygen therapy, and switching to less respiratory-depressant opioids like buprenorphine are also options. But CPAP remains the most proven method for obstructive events. Treatment should be personalized based on the type of apnea you have.

Should I get tested for sleep apnea before starting opioids?

Absolutely. The CDC and American Academy of Sleep Medicine now recommend screening for sleep-disordered breathing before starting long-term opioid therapy, especially if you’re overweight, snore, or have other risk factors. Early detection can prevent life-threatening complications. If your doctor doesn’t offer it, ask for a home sleep test-it’s fast, non-invasive, and covered by most insurance.