Most people think obesity is just about eating too much and moving too little. But if that were true, losing weight would be simple. The truth is far more complicated. Obesity isn’t a failure of willpower-it’s a breakdown in the body’s biological systems that control hunger, fullness, and how energy is used. The science behind it shows that when these systems go wrong, the body fights back against weight loss harder than almost any other condition.

The Brain’s Hunger Control Center

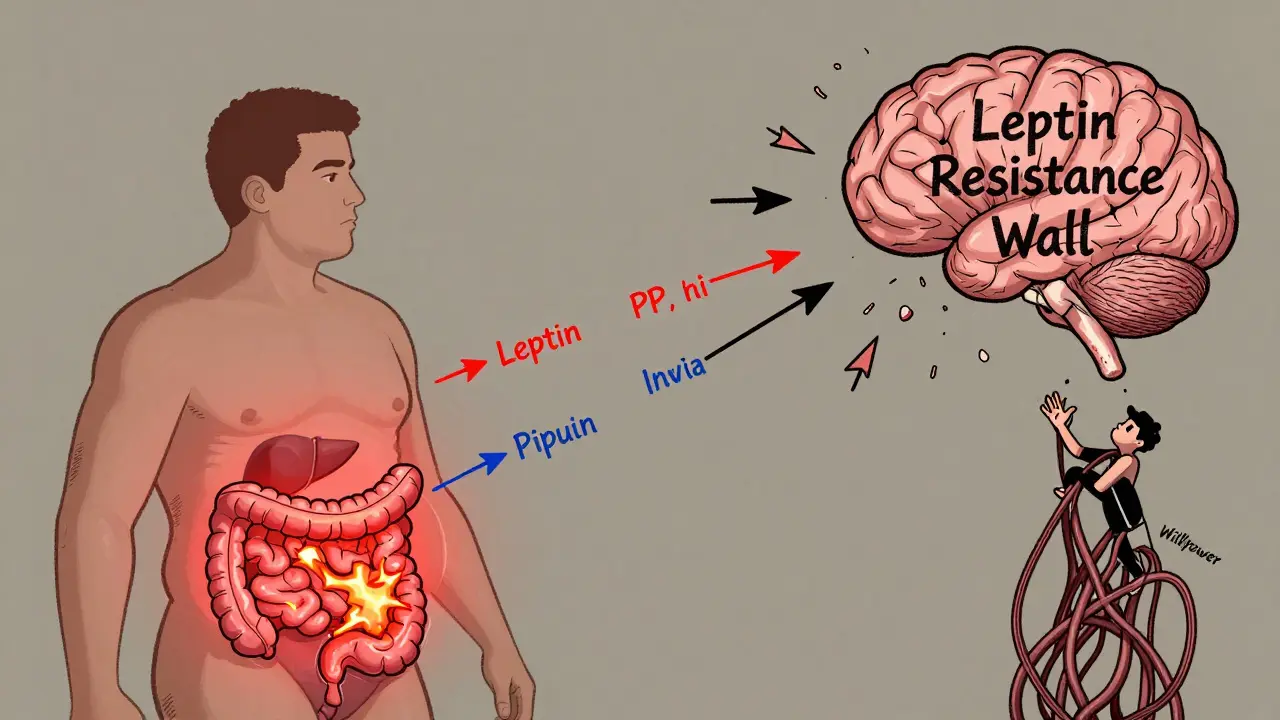

At the core of obesity is a tiny region in the brain called the arcuate nucleus, part of the hypothalamus. This is where your body decides whether to eat or stop eating. Two groups of neurons here act like opposing forces. One group, made up of POMC neurons, tells you to feel full. They release a signal called alpha-MSH, which shuts down appetite. In lab studies, activating these neurons cuts food intake by 25% to 40%. The other group-NPY and AgRP neurons-does the opposite. They scream for food. When scientists turned these neurons on in mice using light (a technique called optogenetics), the animals ate 300% to 500% more in minutes.These neurons don’t work alone. They’re constantly receiving signals from fat tissue, the gut, and the pancreas. Leptin, a hormone made by fat cells, is one of the most important. The more fat you have, the more leptin your body makes. In lean people, leptin levels sit between 5 and 15 ng/mL. In obesity, they jump to 30-60 ng/mL. Logically, you’d think more leptin means less hunger. But here’s the twist: in most people with obesity, the brain stops listening to leptin. This is called leptin resistance. It’s not that the body doesn’t make enough-it’s that the signal gets lost. Think of it like a smoke alarm that’s been deafened by too much noise. The alarm is ringing, but no one hears it.

How Insulin, Ghrelin, and Other Hormones Play Along

Leptin isn’t the only hormone involved. Insulin, which rises after meals, also tells the brain to reduce hunger. Fasting insulin levels are around 5-15 μU/mL; after eating, they can spike to 50-100 μU/mL. In obesity, insulin resistance develops not just in muscles and liver, but also in the brain. That means even when insulin is high, the appetite-suppressing signal doesn’t land.Then there’s ghrelin-the only known hormone that makes you hungry. It spikes right before meals, from about 100-200 pg/mL when you’re fasting to 800-1,000 pg/mL just before you eat. In people with obesity, ghrelin doesn’t drop as much after meals, so the hunger signal lingers. That’s why many people feel hungry even after eating a big meal.

Another key player is pancreatic polypeptide (PP), released after eating. It slows digestion and reduces appetite by blocking NPY/AgRP neurons. But in 60% of people with diet-induced obesity, PP levels are abnormally low-only 15-25 pg/mL instead of the normal 50-100 pg/mL. That means the body’s natural ‘stop eating’ signal is weak from the start.

Why Dieting Often Fails: The Body Fights Back

When you lose weight, your body doesn’t just accept it. It thinks you’re starving. Leptin levels drop sharply. Ghrelin rises. Your metabolism slows down. Studies show that after losing 10% of body weight, resting energy expenditure can drop by 200-400 calories per day-more than what’s burned by a 30-minute walk. This isn’t laziness. It’s biology.And it’s not just hormones. The brain’s reward system gets rewired. Highly processed, sugary, fatty foods hijack the dopamine pathways. Over time, the brain needs more of these foods to feel the same pleasure. That’s why cutting out junk food feels so hard-it’s not just a habit. It’s a neurological adaptation.

The Hidden Role of Inflammation and Cellular Stress

Obesity isn’t just about fat storage-it’s about chronic low-grade inflammation. Fat tissue, especially around the belly, releases inflammatory molecules that interfere with insulin and leptin signaling. One key player is JNK, a stress-response protein that becomes overactive in obesity. JNK blocks the PI3K/AKT pathway, which is essential for leptin to work. This is why some people can have high leptin levels but still feel starving.Another pathway, mTOR, helps regulate how cells respond to nutrients. When it’s overactive, it promotes fat storage and reduces energy burning. Animal studies show that stimulating mTOR in the brain cuts food intake by 25%, but in obesity, this system becomes dysfunctional. Meanwhile, BMP4-a protein linked to fat cell development-has been shown to reduce appetite in obese mice by 20%. These discoveries point to new drug targets that could reset these broken signals.

Gender, Age, and Other Factors That Change the Game

Not everyone’s body responds the same way. Women, especially after menopause, are at higher risk. Estrogen helps regulate fat distribution and energy use. When estrogen drops after menopause, women gain 12-15% more belly fat within five years. Studies in mice without estrogen receptors show they eat 25% more and burn 30% less energy. That’s why weight gain after menopause isn’t just about aging-it’s hormonal.Children with Prader-Willi syndrome have a genetic condition that causes extreme hunger. Their PP levels are dangerously low, and their brains don’t respond to fullness signals. This isn’t rare-it’s a window into how broken appetite regulation can look. Even without a genetic disorder, many people with obesity show similar patterns: low PP, high ghrelin, leptin resistance.

And then there’s sleep. People with narcolepsy, a condition linked to low orexin (a brain chemical that regulates wakefulness and appetite), have two to three times the rate of obesity. Orexin levels drop by 40% in obese individuals, but spike in people with night-eating syndrome. This shows how deeply appetite is tied to circadian rhythms-and how disrupted sleep can fuel weight gain.

What’s Working: New Treatments Based on the Science

For decades, obesity treatment was limited to calorie counting and exercise. Now, we have drugs that actually target the biology. Setmelanotide, a drug that activates the melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R), works miracles in rare genetic forms of obesity. In people with POMC or LEPR mutations, it cuts weight by 15-25%. It’s not a miracle for everyone-but it proves the science works.Even more promising is semaglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist. Originally developed for type 2 diabetes, it reduces appetite by slowing gastric emptying and directly acting on the hypothalamus. In clinical trials, people lost an average of 15% of their body weight. That’s more than most bariatric surgeries achieve. It doesn’t just suppress hunger-it helps reset the brain’s set point.

And in 2022, researchers discovered a new group of neurons next to the hunger and fullness cells in the arcuate nucleus. When activated, they shut down eating in under two minutes. This could lead to entirely new therapies-ones that don’t rely on hormones, but on direct brain stimulation.

The Big Picture: Obesity Is a Disease, Not a Choice

The science is clear: obesity is a chronic disease of dysregulated biology. It’s not caused by poor discipline. It’s caused by broken signals between fat, brain, gut, and liver. The body fights weight loss because it’s trying to survive. That’s why quick fixes fail. Real progress comes from understanding these pathways and treating them like we treat diabetes or hypertension-with medication, lifestyle, and long-term support.Global obesity rates have nearly tripled since 1975. In the U.S., over 42% of adults have obesity. The cost? $173 billion a year in healthcare spending. But the real cost is the human one-lost health, mobility, and quality of life. The good news? We’re finally developing treatments that work at the root cause. And that changes everything.

Is obesity just caused by eating too much?

No. While overeating plays a role, the real issue is how the body regulates hunger and energy use. Most people with obesity have hormonal imbalances like leptin resistance, low pancreatic polypeptide, and abnormal ghrelin levels. Their brains are wired to crave food and burn fewer calories-even when they eat less. It’s not a lack of willpower; it’s a biological malfunction.

Why do I feel hungrier after losing weight?

After weight loss, your body thinks it’s in starvation mode. Leptin levels drop sharply, ghrelin rises, and your metabolism slows by 200-400 calories per day. These are survival mechanisms. Your brain is trying to restore the weight it lost. This is why many people regain weight-it’s not laziness, it’s biology.

Can leptin supplements help me lose weight?

No. Most people with obesity already have very high leptin levels. The problem isn’t low leptin-it’s that the brain doesn’t respond to it. This is called leptin resistance. Taking more leptin won’t fix it. In fact, clinical trials with leptin supplements failed in obese individuals. The exception is rare genetic cases of leptin deficiency, which affect fewer than 50 people worldwide.

How do drugs like semaglutide work?

Semaglutide mimics GLP-1, a gut hormone that signals fullness to the brain. It slows stomach emptying, reduces appetite, and directly acts on the hypothalamus to suppress hunger signals. In trials, it led to 15% average weight loss-not by starving you, but by resetting your brain’s hunger set point. It’s one of the first treatments that actually targets the biology of obesity.

Why do women gain more belly fat after menopause?

Estrogen helps control fat distribution and energy use. After menopause, estrogen drops, and the body shifts fat storage to the abdomen. Studies show women lose about 12-15% more belly fat within five years after menopause. In mice without estrogen receptors, food intake increases by 25% and energy expenditure drops by 30%. This isn’t aging-it’s hormonal change.

Are there new treatments on the horizon?

Yes. In 2022, scientists found a new group of neurons in the hypothalamus that can shut down eating within two minutes of activation. This opens the door to brain-targeted therapies that don’t rely on hormones. Currently, 17 new drugs are in phase 2 or 3 trials targeting appetite, metabolism, or both. Combination therapies-like GLP-1 with GIP or amylin-are showing even stronger results than single drugs.

Dayanara Villafuerte

So let me get this straight... we're telling people their bodies are broken, but the solution is still 'eat less, move more'? 🤦♀️ I've seen 3 different endocrinologists and none of them gave me a damn pill that worked. Now we got semaglutide? Cool. Took 50 years to catch up to what diabetics got in 2003. #BiologicalRealityCheck 🍔💔