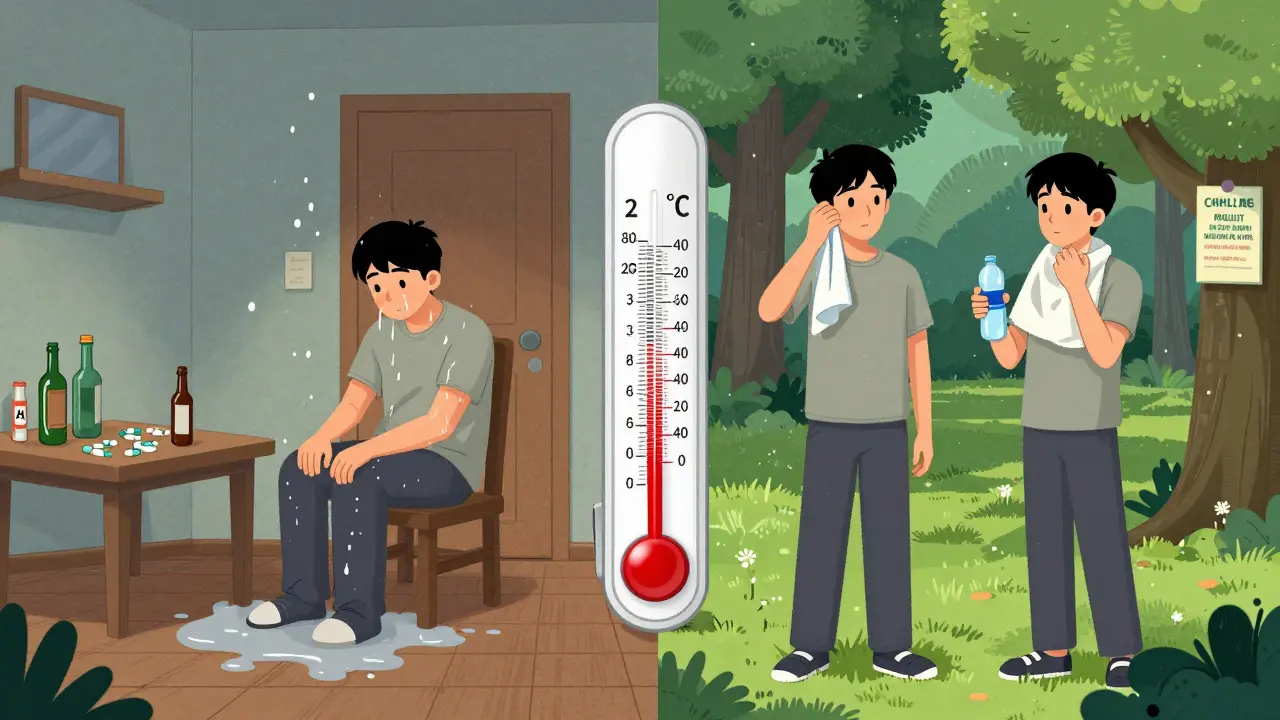

When the temperature hits 24°C (75°F) or higher, your body is under stress. For someone using drugs, that stress can turn deadly. Heatwaves don’t just make you sweaty and tired-they change how your body processes drugs, increase your chance of overdose, and strip away the safety margins you might normally rely on. This isn’t theoretical. In New York City, emergency calls for overdoses jumped 22% during heat advisories between 2018 and 2022. In the Pacific Northwest’s 2021 heat dome, overdose deaths spiked even though the region wasn’t used to extreme heat. People who use drugs, especially those without stable housing or access to medical care, are caught in a dangerous crossfire: rising temperatures and weakened bodily defenses.

Why Heat Makes Overdose More Likely

Your body works hard to stay cool. When it’s hot, your heart pumps faster-up to 25 beats per minute more at rest. If you’ve taken a stimulant like cocaine or methamphetamine, your heart is already working overtime. Add heat on top, and you’re pushing your cardiovascular system past its limit. This combination is a leading cause of sudden death during heatwaves. Dehydration plays a big role too. Losing just 2% of your body weight in fluids-something that happens easily in high heat-concentrates drugs in your bloodstream. That means a dose you normally take could become stronger, like switching from a 10mg pill to a 12mg one without realizing it. For opioids, heat reduces your body’s ability to compensate for slowed breathing. Normally, your body kicks in to keep you breathing if your drug dose is too high. Heat weakens that safety net by 12-18%, making respiratory failure more likely. Medications for mental health make things worse. About 70% of antipsychotics and 45% of antidepressants lose effectiveness or cause worse side effects in high heat. Someone managing depression or psychosis with these drugs might feel more confused, dizzy, or disoriented when it’s hot-making it harder to recognize early signs of overdose or know when to ask for help.Who’s Most at Risk

People experiencing homelessness are especially vulnerable. In the U.S., around 580,000 people sleep outside or in shelters on any given night. Nearly 4 in 10 of them have a substance use disorder. These individuals rarely have access to air-conditioned spaces, clean water, or medical support during heat emergencies. They’re also more likely to use drugs alone, which means no one is there to administer naloxone or call 911 if things go wrong. People with chronic illnesses-heart disease, kidney problems, or diabetes-are also at higher risk. Many of them take medications that interfere with body temperature control. And if they’re using drugs on top of that, their body has even less ability to cope. Even people who don’t consider themselves at risk can be caught off guard. Someone who usually uses in a cool apartment might go outside to buy drugs on a hot day, or stay in a non-air-conditioned room during a heatwave. That small change in environment can be enough to trigger an overdose.

What You Can Do: Practical Harm Reduction Steps

The good news? You can reduce your risk. Here’s how:- Reduce your dose and frequency. During heatwaves, cut your usual amount by 25-30%. Don’t wait until you feel sick to scale back. Start early. Your body doesn’t handle drugs the same way when it’s hot.

- Hydrate constantly. Drink one cup (8 oz) of cool water every 20 minutes-even if you don’t feel thirsty. Avoid alcohol and caffeine. They make dehydration worse. Electrolyte packets (like those used for athletes) help replace lost salts and minerals.

- Never use alone. If you’re going to use, make sure someone is nearby who knows how to use naloxone and can call for help. If you’re alone, use the buddy system: text a friend before you start, and set a timer to check in with them in 20 minutes.

- Use in a cool place. If you have access to a library, community center, or cooling station, go there. Even a shaded park bench is better than a hot car or sidewalk. Avoid direct sunlight.

- Know the signs of heat illness. Dizziness, nausea, confusion, rapid heartbeat, and dry skin are red flags. If you feel this way, stop using immediately. Cool down, drink water, and rest. These symptoms can quickly turn into heatstroke-and heatstroke can mask or worsen overdose symptoms.

What Communities and Services Can Do

Harm reduction groups have shown what works. In Philadelphia, they hand out cooling kits with misting towels, water bottles, and electrolyte sachets. In Vancouver, they opened seven air-conditioned respite centers next to supervised consumption sites. During the 2021 heat dome, that program cut heat-related overdose deaths by 34%. In Maricopa County, Arizona, volunteers trained in naloxone use made over 12,000 wellness checks during one summer. They didn’t judge. They just asked, “Are you okay?” and offered water, shade, or a ride to a cooling center. But too many places still ignore this issue. Only 12 out of 50 U.S. states include drug users in their official heat emergency plans. Many shelters turn away people who are actively using drugs-even during life-threatening heat. Police in some cities have confiscated cooling supplies from outreach workers. Real change means policy. Cities need to treat heat-related overdose risk like any other public health emergency. That means:- Opening cooling centers that don’t require sobriety

- Training first responders to recognize drug-related heat illness

- Supplying naloxone and hydration kits at shelters and food banks

- Coordinating between public health, emergency services, and harm reduction groups

What to Do If You See Someone in Trouble

You don’t need to be a medic to help. If someone looks unresponsive, confused, or overheated:- Call emergency services immediately. Say: “I think this person is having an overdose and heat illness.”

- Move them to a cooler place-shade, air conditioning, even a wet towel on their neck helps.

- Give them cool water if they’re conscious and able to swallow.

- Administer naloxone if you have it and suspect opioids are involved. It’s safe even if you’re not sure.

- Stay with them until help arrives. Don’t leave them alone.

What’s Changing in the Future

Climate change isn’t slowing down. By 2050, we could see 20-30 extra days each year above the 24°C threshold that triggers higher overdose risk. Research is now looking at how heat changes gut bacteria, which might affect how drugs are broken down in the body. That could lead to new guidelines for dosing during heatwaves. The World Health Organization now advises treatment centers to adjust medication doses during extreme heat. For example, buprenorphine becomes 23% less effective above 30°C. That means people on this medication might need a different plan when it’s scorching outside. The bottom line? Heat and drugs are a deadly mix. But it’s not inevitable. We know what works: hydration, reduced doses, cooling spaces, and community support. What’s missing is the will to make it happen at scale. If you use drugs, plan ahead. If you care about someone who does, talk to them now-before the next heatwave hits. Don’t wait for a crisis. A few simple steps can save a life.Can heat make a drug overdose worse even if I’m not using stimulants?

Yes. While stimulants like cocaine and meth increase heart strain in heat, opioids are just as dangerous. Heat reduces your body’s ability to compensate for slowed breathing, which is the main cause of opioid overdose deaths. Even if you’re using only opioids, a hot environment can push you past your safety limit without you realizing it.

Should I stop using drugs entirely during a heatwave?

That’s a personal decision, but if you continue using, you must reduce your dose and take extra precautions. Quitting cold turkey during a heatwave can be risky too-withdrawal symptoms like sweating, nausea, and rapid heartbeat can be mistaken for heat illness. If you’re considering stopping, talk to a healthcare provider about a safe plan. Otherwise, reduce your amount by 25-30%, stay hydrated, and never use alone.

Are cooling centers safe for people who use drugs?

The best ones are. Some shelters turn people away if they’re actively using, but places like Vancouver’s Cooling and Care centers allow drug use in a supervised, safe space. Look for centers that partner with harm reduction organizations-they’re more likely to offer water, naloxone, and non-judgmental support. If a center refuses you because you’re using drugs, find another one. Your life matters more than their rules.

Can I use ice packs or cold showers to cool down while using drugs?

Yes, but with caution. Applying ice packs to your neck, armpits, or groin can help lower body temperature safely. A cool (not icy) shower is also effective. Avoid ice baths or extreme cold-sudden temperature drops can shock your system, especially if you’ve taken drugs. Focus on gradual cooling. Drink water at the same time. Don’t rely on cold exposure alone; combine it with dose reduction and hydration.

What if I’m on medication for mental health and using drugs?

This combination is especially risky in heat. Many psychiatric medications-like antipsychotics and antidepressants-reduce your body’s ability to regulate temperature. They can also interact unpredictably with drugs, increasing side effects like dizziness, confusion, or heart problems. Talk to your doctor before a heatwave about adjusting your medication or creating a safety plan. Don’t stop your meds without guidance, but do reduce drug use and stay cool.

How do I know if I’m dehydrated?

Signs include dark yellow urine, dry mouth, dizziness, headache, and feeling unusually tired or confused. If you haven’t urinated in 4-6 hours, you’re likely dehydrated. Even if you don’t feel thirsty, drink water every 20 minutes during heat. Don’t wait until you’re thirsty-by then, you’re already low on fluids.

Is naloxone still effective during a heatwave?

Yes. Naloxone works the same way regardless of temperature. If you suspect an opioid overdose, give it immediately. Heat doesn’t reduce its effectiveness. But remember: naloxone only reverses opioid overdoses. If someone is overdosing from stimulants like cocaine or meth, naloxone won’t help. Still, call emergency services-cooling them down and giving fluids can save their life.

Where can I find a cooling center near me?

Call your local public health department or search online for “cooling centers + [your city].” Many libraries, community centers, and religious buildings open their doors during heat emergencies. If you’re unsure, ask a harm reduction organization-they often have updated lists. In Melbourne, check with the Department of Health or local needle and syringe programs. They know which places are safe and welcoming.

Alvin Bregman

heat and drugs is a bad combo no doubt but why do we keep acting like this is new news