When Medications Stop Working, Surgery Becomes an Option

If you’ve tried two or more anti-seizure medications and still have seizures every week-or even every day-you’re not alone, and you’re not out of options. About 1 in 3 people with epilepsy don’t respond to drugs, no matter how many they try. This isn’t failure on your part. It’s called drug-resistant epilepsy, and it’s a medical reality, not a personal one. For many of these people, surgery isn’t a last resort-it’s the best chance to live a life with fewer or no seizures.

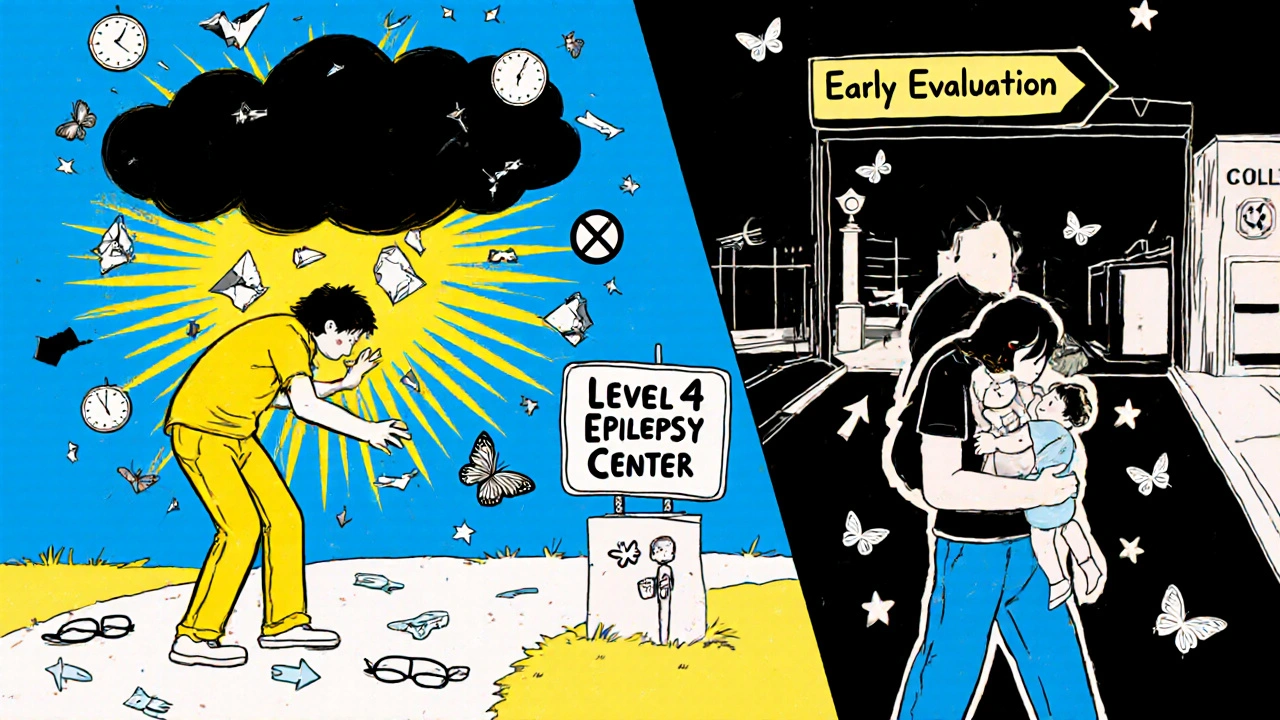

Forget the old idea that you need to wait two years after medications fail before considering surgery. That rule is outdated. Today, experts say: if two drugs haven’t worked, get evaluated. You don’t need to suffer for years hoping the next pill will be the one. The goal isn’t just to reduce seizures-it’s to restore your life. Can you drive again? Go back to work? Sleep through the night without fear? Surgery makes that possible for many.

Who Is a Good Candidate for Epilepsy Surgery?

Not everyone with drug-resistant epilepsy is a candidate. But many more people than you think could be. The key is finding where the seizures start. If they come from one clear spot in the brain-a focal onset-surgery has a high chance of success. The most common type is mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis. This is where the hippocampus, a structure deep in the temporal lobe, is scarred or shrunken. It’s a well-defined target, and removing it often stops seizures completely.

For adults, candidacy comes down to three things:

- You’ve tried at least two appropriate anti-seizure medications and still have disabling seizures (usually one or more per month).

- Your seizures originate from a part of the brain that can be safely removed or disconnected without causing major damage.

- You and your family understand what surgery means, including the risks and possible outcomes.

For children, the rules are even more urgent. If a child has infantile spasms, tuberous sclerosis, or Rasmussen’s encephalitis, surgery isn’t optional-it’s often the only way to prevent permanent brain damage. These conditions rarely respond to drugs. Waiting only makes things worse.

But here’s the catch: many people never get evaluated. A 2022 study found that fewer than 1% of people with drug-resistant epilepsy in the U.S. are referred to a specialized epilepsy center. That means tens of thousands are missing out. The reason? Fear, misinformation, or just not knowing where to turn.

What Happens During the Evaluation?

Surgery isn’t decided on a single MRI or EEG. It’s a process that takes weeks and involves a team of specialists: epileptologists, neurosurgeons, neuropsychologists, and nurses who know exactly what to look for.

The evaluation usually includes:

- Video-EEG monitoring for 5 to 7 days. You’ll be hooked up to electrodes while cameras record your seizures. This helps doctors pinpoint exactly where and how they start.

- High-resolution 3T MRI with special epilepsy protocols. These scans look for subtle scars, malformations, or shrinkage in the brain that standard MRIs miss.

- FDG-PET scan, which shows areas of the brain using less glucose-often the seizure focus.

- Neuropsychological testing to measure memory, language, and thinking skills. This helps predict what might change after surgery.

- Intracranial EEG (if needed). Wires are placed directly on the brain surface to get a clearer signal. This is invasive, but sometimes necessary when non-invasive tests are unclear.

It’s not just about finding the seizure zone. It’s about making sure removing it won’t take away your ability to speak, remember, or move. That’s why the team spends so much time testing and cross-checking data. If the seizure area overlaps with critical functions, they might try mapping the brain with electrical stimulation to see if they can safely remove it.

What Are the Risks?

Any brain surgery carries risk. But for many, the risk of continuing seizures is greater.

For a common procedure like a temporal lobectomy (removing part of the temporal lobe), the most likely risks are:

- Transient issues (happening in 5-10% of cases): Swelling, temporary weakness, trouble finding words, or mood changes. These usually go away in weeks.

- Permanent deficits (1-2% risk): Memory problems, especially if the dominant (usually left) side is operated on. Some people notice difficulty remembering names or new information. Vision changes can happen if the surgery affects the visual pathway.

- Infection or bleeding (less than 1%): Rare, but possible with any brain surgery.

For less invasive options like laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT), risks are lower-around 2-3% for permanent side effects. LITT uses a thin laser probe guided by MRI to heat and destroy the seizure focus. It’s not for everyone, but for certain cases, it’s a great alternative to open surgery.

One of the biggest fears? Losing your memory or personality. While some memory changes can happen, especially with left-sided surgery, most patients report no major loss. In fact, many say their thinking improves because they’re not foggy from meds or exhausted from seizures anymore.

What Can You Expect After Surgery?

Results vary, but they’re often life-changing.

For people with temporal lobe epilepsy and hippocampal sclerosis:

- 65-70% become completely seizure-free within two years.

- 80-85% have at least a 90% reduction in seizures.

For other focal epilepsies-like those from tumors or cortical dysplasia-the success rate is still strong, around 50-60% seizure freedom.

But here’s the real win: quality of life. In a 2021 study, 79% of patients who had surgery said they could drive for the first time in years. Many returned to work, stopped relying on caregivers, and started sleeping through the night. One patient on Reddit wrote: “I had 15-20 seizures a day before surgery. Three years later, zero. I got my license. I started college. I didn’t think that was possible.”

For children, the benefits can be even more dramatic. Some who were nonverbal or in wheelchairs begin talking, walking, and learning after surgery. Early intervention can change a child’s entire developmental path.

Not everyone is cured. About 15-20% of people who go through the full evaluation aren’t candidates because their seizures come from too many areas or can’t be localized. Others have surgery but still have occasional seizures-though often far fewer and less severe.

Why So Few People Get Surgery?

There’s a huge gap between who could benefit and who actually gets help. In the U.S., about 1.2 million people have drug-resistant epilepsy. Only 5,000 surgeries are done each year. That’s less than 1 in 200.

Why?

- Fear. Half of people referred to surgery decline because they’re terrified of brain surgery.

- Delayed referrals. A 2022 survey found 63% of patients waited over five years after becoming drug-resistant to get evaluated. Some waited over a decade.

- Insurance hurdles. Nearly half of initial requests for surgery are denied. But 78% get approved after appeal.

- Doctor ignorance. Nearly half of neurologists still can’t correctly define drug-resistant epilepsy. Many still believe surgery is only for “last-resort” cases.

Geography matters too. 85% of the best epilepsy centers are in big cities. If you live in a rural area, getting to one can mean driving hours-or giving up.

What’s New in Epilepsy Surgery?

Technology is making surgery safer and more accessible.

Laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT) is growing fast. Instead of opening the skull, a laser is inserted through a tiny hole. It heats and destroys the seizure focus under real-time MRI control. Recovery is faster-often just a few days in the hospital. Success rates are around 55% at one year, slightly lower than open surgery, but with far fewer complications.

Responsive neurostimulation (RNS) is another option. A device is implanted in the skull that detects abnormal brain activity and delivers a tiny pulse to stop seizures before they start. It’s not a cure, but it can cut seizures by half or more. The FDA recently expanded its use to include some generalized epilepsies, opening the door for more people.

And there’s a global push to fix the referral crisis. The International League Against Epilepsy launched a program in 2023 to train doctors worldwide to refer patients earlier. Their goal? Increase referral rates to 5% annually by 2025.

What Should You Do Next?

If you or someone you love has drug-resistant epilepsy, here’s what to do now:

- Track your seizures. Write down frequency, duration, triggers, and how you feel afterward. A diary is your best tool.

- Ask your neurologist: “Am I a candidate for epilepsy surgery?” Don’t wait for them to bring it up.

- Find a Level 4 epilepsy center. These are the only ones with the full team and technology to do a proper evaluation. You can find them through the National Association of Epilepsy Centers.

- Bring someone with you to appointments. It’s a lot to take in. A second set of ears helps.

- Connect with others. Online communities like r/epilepsy on Reddit have real stories from people who’ve been through it.

Don’t let fear or delay steal your future. Surgery isn’t a gamble-it’s a calculated step with proven results. The earlier you act, the better your chances-not just of stopping seizures, but of getting your life back.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can epilepsy surgery cure me completely?

For some people, yes. About 65-70% of those with temporal lobe epilepsy and hippocampal sclerosis become completely seizure-free after surgery. For others, seizures are greatly reduced-by 80% or more. But not everyone is cured. Success depends on where the seizures start, how well they can be mapped, and whether the area can be safely removed.

Is epilepsy surgery dangerous?

All brain surgery carries risks, but modern techniques make it safer than ever. For a standard temporal lobectomy, the chance of permanent brain damage is 1-2%. Temporary side effects like memory issues or word-finding trouble happen in 5-10% of cases but usually fade. Less invasive options like LITT have even lower risks, around 2-3%. The bigger risk may be not doing anything-ongoing seizures raise the chance of injury, depression, and even sudden death (SUDEP).

How long does the evaluation take?

The full evaluation usually takes 2 to 6 weeks. It includes 5-7 days of video-EEG monitoring, high-res MRI, PET scans, neuropsychological tests, and sometimes invasive monitoring. The goal is to be thorough. Rushing can lead to wrong decisions. Some cases take longer if the seizure focus is hard to find.

Will I still need to take medicine after surgery?

Almost always, yes-at least at first. Most people stay on at least one anti-seizure medication for a year or two after surgery. If seizures stay gone, doctors slowly reduce the dose. About half of seizure-free patients can stop all meds within 2-3 years. Others need to stay on a low dose long-term. It’s not failure-it’s prevention.

Can children have epilepsy surgery?

Yes-and often, they benefit more than adults. Children’s brains are more adaptable. If a seizure focus is found early, removing it can prevent lifelong disability. Conditions like infantile spasms, tuberous sclerosis, or Rasmussen’s encephalitis often require surgery as soon as possible. The goal isn’t just to stop seizures-it’s to protect brain development.

What if I’m not a candidate for surgery?

You still have options. Devices like responsive neurostimulation (RNS) or vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) can reduce seizures by 50% or more. Dietary therapies like the ketogenic diet also help some people. Clinical trials for new drugs and devices are ongoing. And even if surgery isn’t right now, your situation can change. Re-evaluation every few years is important.

robert cardy solano

My cousin had temporal lobe surgery last year. Zero seizures now. She drives, works full-time, and actually remembers where she put her keys. I used to think brain surgery was a last resort. Turns out it was the first thing she should’ve done.