Ringworm Spread Risk Calculator

Personal Risk Assessment

Enter your current habits to see your risk level for ringworm spreading to other body parts.

Risk Assessment Results

When you spot a red, itchy patch that looks like a ring, you’re probably dealing with Ringworm (Tinea) is a common superficial fungal infection caused by dermatophytes that feeds on keratin in skin, hair and nails. Most people wonder whether that one spot can jump to other parts of the body. The short answer is yes - the fungus can move, but the odds depend on a handful of factors you can control.

How Ringworm Moves Around

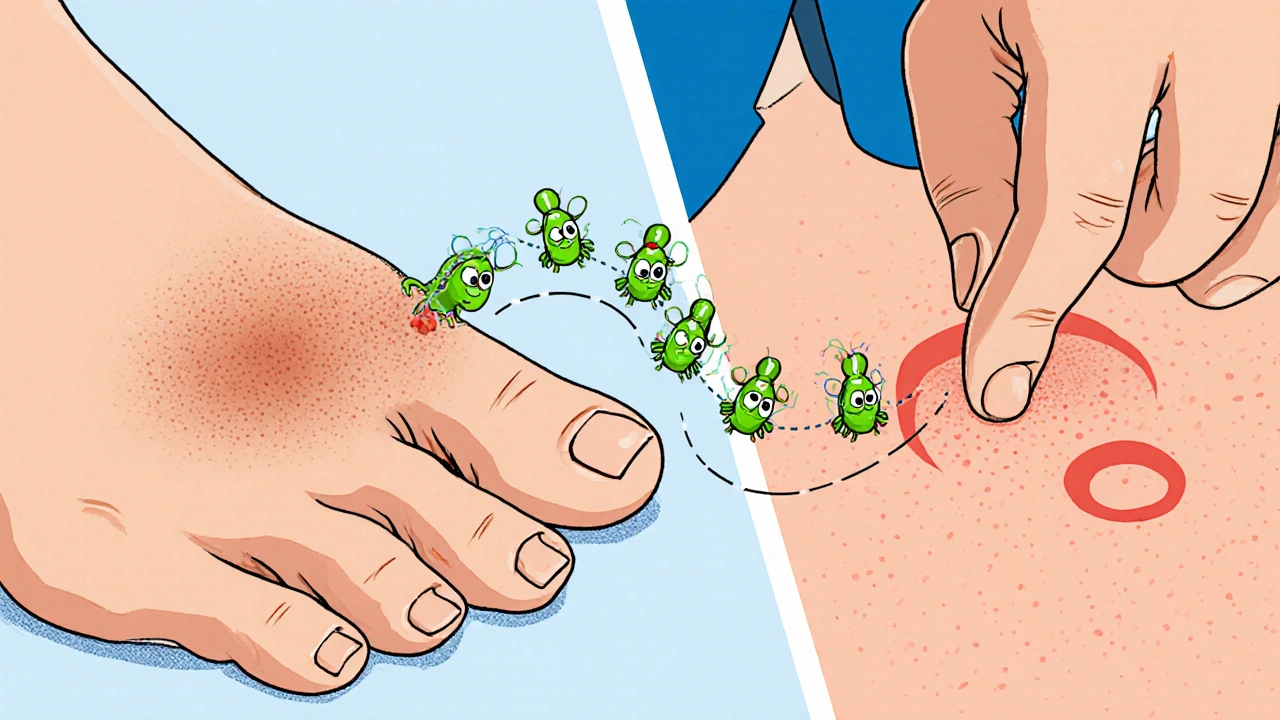

Ringworm spreads in two main ways: external (from another person, animal or object) and internal - what doctors call autoinoculation. External spread follows the classic rule of “touch‑contaminate‑touch”. If you touch a ringworm‑infected surface and then touch a clean area of skin, the spores can lodge and start a new infection.

Autoinoculation is the culprit when the infection jumps from, say, your foot to your groin. It usually happens because the fungus loves warm, moist environments, and you provide that by scratching or rubbing the rash onto another spot.

ringworm spread is driven by three simple actions:

- Direct skin‑to‑skin contact with the infected area.

- Contact with contaminated items - towels, clothing, bedding or gym mats.

- Self‑transfer caused by scratching, shaving or applying medication with unclean hands.

Common Body Sites and Their Risk Levels

Different species of Dermatophytes are adapted to specific body zones. Here’s a quick rundown:

| Type | Typical Site | Spread Risk Within Body |

|---|---|---|

| Tinea corporis | Arms, trunk, legs | Medium - easy to scratch onto nearby skin |

| Tinea cruris | Groin, inner thighs | High - moisture encourages rapid growth |

| Tinea pedis | Feet (especially between toes) | High - often spreads to toenails and the groin |

| Tinea capitis | Scalp | Low - usually stays on the head unless hair is moved |

| Tinea unguium | Nails | Very low - spreads outward rather than upward |

Notice that the areas that stay moist (groin, feet) have the highest internal spread risk. That’s why athletes, hikers and anyone who wears tight, sweaty shoes are prime candidates.

Why the Fungus Loves to Migrate

Three biological drivers power the move:

- Moisture - Dermatophytes thrive where sweat builds up. The Immune system can usually keep them in check, but damp skin creates a safe harbor.

- Keratin availability - The fungus feeds on dead skin cells. Scratching strips off the outer layer, exposing fresh keratin for the spores to munch on.

- Micro‑trauma - Small cuts or abrasions from shaving or sports injuries act like doorways for the spores.

If you combine moisture, scratching, and a tiny skin break, you’ve got a perfect recipe for the fungus to hop to a new spot.

Practical Steps to Stop the Spread

Here’s a checklist you can start using today:

- Wash hands thoroughly after touching any rash. Use antibacterial soap and dry the hands completely.

- Keep the affected area dry. Apply a light dusting of talc or a moisture‑wicking powder after showering.

- Don’t share towels, clothing, or socks. If you must, use a hot‑water wash (60 °C / 140 °F) and a dryer cycle.

- Avoid scratching. If the itch is unbearable, use a cool compress or an over‑the‑counter antihistamine.

- Apply an antifungal cream such as clotrimazole 1% or terbinafine 1% twice daily for at least two weeks after the rash clears.

- For extensive or stubborn cases, see a doctor. Oral antifungals (e.g., itraconazole) may be needed, especially if the infection has jumped to nails or multiple body parts.

Remember, topical treatment alone works best when the fungus hasn’t spread deeply or to the nails. Once it’s in the nail bed, oral medication is usually required.

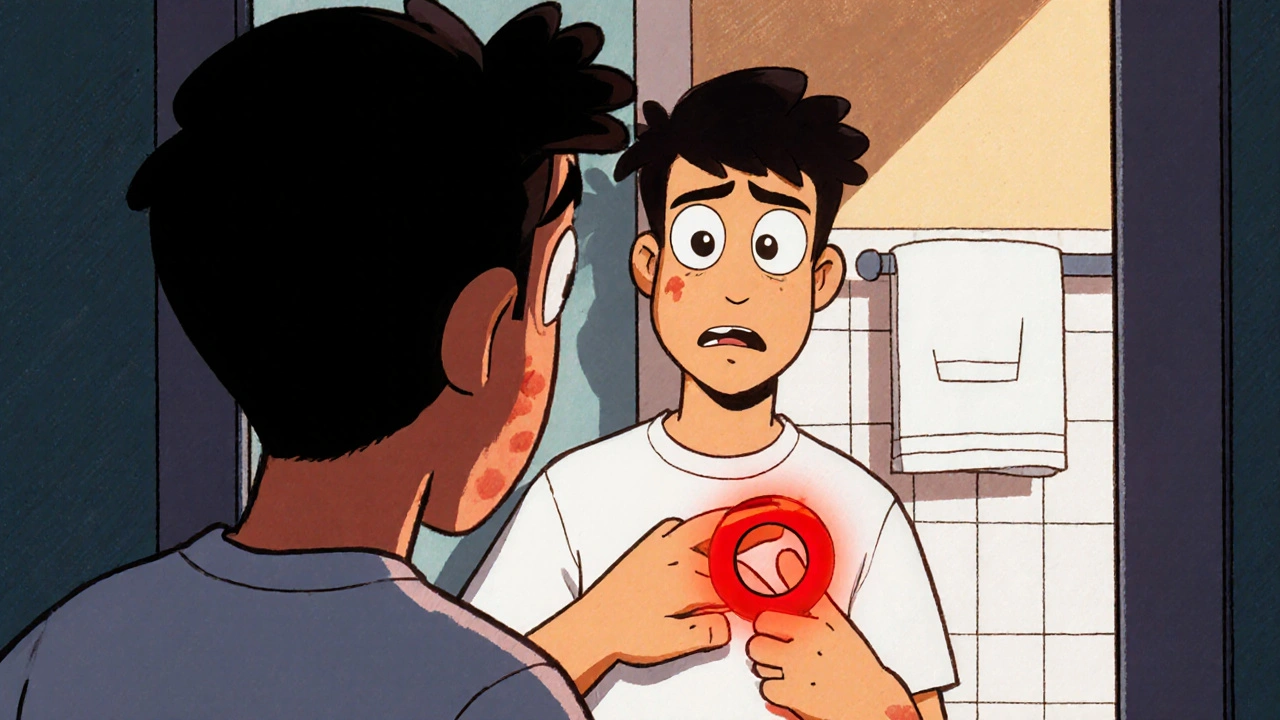

When to Seek Professional Help

If you notice any of these red flags, book an appointment:

- The rash spreads quickly despite home treatment.

- You develop new lesions in a different body region within a week.

- The skin becomes very thick, scaly, or cracks open.

- You have a weakened immune system (e.g., diabetes, HIV, chemotherapy).

- Painful swelling or signs of bacterial infection (pus, fever).

A doctor can confirm the diagnosis with a simple skin scraping and may prescribe stronger topical agents or a short course of oral antifungals.

Quick Reference Checklist

- Keep skin clean and dry.

- Avoid sharing personal items.

- Wash hands after contact.

- Use antifungal cream for at least 2 weeks after symptoms disappear.

- Watch for new spots - treat them early.

- Consult a clinician if spread is rapid or you have health‑risk factors.

Can I get ringworm from my own skin?

Yes. Autoinoculation lets the fungus move from one spot to another on the same person, especially if you scratch or use contaminated towels.

How long does it take for a new spot to appear after spreading?

New lesions can show up within 3‑7 days, depending on the fungus species and how much moisture is present.

Is ringworm contagious while I’m using cream?

The infection remains contagious until the fungus is fully eradicated, usually a week or two after the rash looks clear. Keep hygiene strict during treatment.

Can pets give me ringworm that then spreads on my body?

Yes. Cats and dogs can carry dermatophytes. If you get infected from a pet, the same autoinoculation rules apply, so treat yourself promptly and wash pet bedding.

What’s the best way to prevent ringworm from moving to my groin?

Keep the groin area dry, wear breathable cotton underwear, and avoid scratching. Apply a thin layer of antifungal powder after showers if you’re prone to moisture.

Kirsten Youtsey

The pathophysiology of tinea corporis elucidates a sophisticated interplay between keratinophilic dermatophytes and the host’s cutaneous microenvironment.

Notwithstanding the superficial nature of the infection, epidemiologists have observed that the organism capitalizes on minute breaches in the stratum corneum to propagate.

Consequently, the notion that a solitary lesion cannot migrate is a gross oversimplification propagated by overly zealous consumer health pamphlets.

Empirical data from dermatological surveys indicate a statistically significant correlation between inadequate hygiene practices and autoinoculation rates.

Moreover, clandestine commercial interests have, in my estimation, suppressed comprehensive public education in favor of selling redundant antifungal topicals.

The proprietary formulations are marketed as panaceas, yet they merely address symptomatic relief while the underlying mycotic reservoir persists.

A cursory glance at the literature reveals that sustained dryness of the affected site, combined with diligent hand hygiene, dramatically curtails spore dissemination.

Patients who neglect these basic precautions inadvertently furnish the fungus with a vector for intra‑body migration.

It is also worth noting that the warm, moist milieu of the groin and interdigital spaces furnishes an ideal incubator for accelerated growth.

Thus, individuals predisposed to hyperhidrosis should be particularly vigilant in employing absorbent powders and breathable apparel.

While over‑the‑counter creams such as clotrimazole possess fungistatic properties, their efficacy is contingent upon uninterrupted application for the recommended duration.

Premature cessation of therapy, a practice frequently encouraged by cost‑saving insurers, precipitates a relapse and potential spread to adjacent dermal territories.

In the event of refractory infection, oral azoles may be prescribed, though their systemic side‑effect profile necessitates judicious use.

From a public health perspective, the dissemination of accurate, unembellished information remains the most potent antidote to the insidious propagation of ringworm.

Regrettably, the current paradigm favors sensationalized headlines over methodical patient education.

Hence, a disciplined regimen of hygiene, environmental decontamination, and adherence to pharmacologic protocols constitutes the most reliable bulwark against intra‑body spread.