What Deep Brain Stimulation Actually Does for Parkinson’s

Deep Brain Stimulation, or DBS, isn’t a cure for Parkinson’s. It doesn’t stop the disease from progressing. But for the right person, it can turn a day full of freezing, shaking, and medication side effects into one where movement feels more predictable, more controlled. Think of it like a pacemaker for your brain. Electrodes are placed in specific spots deep inside the brain, and they send out tiny electrical pulses that help smooth out the chaotic signals causing tremors, stiffness, and slowness.

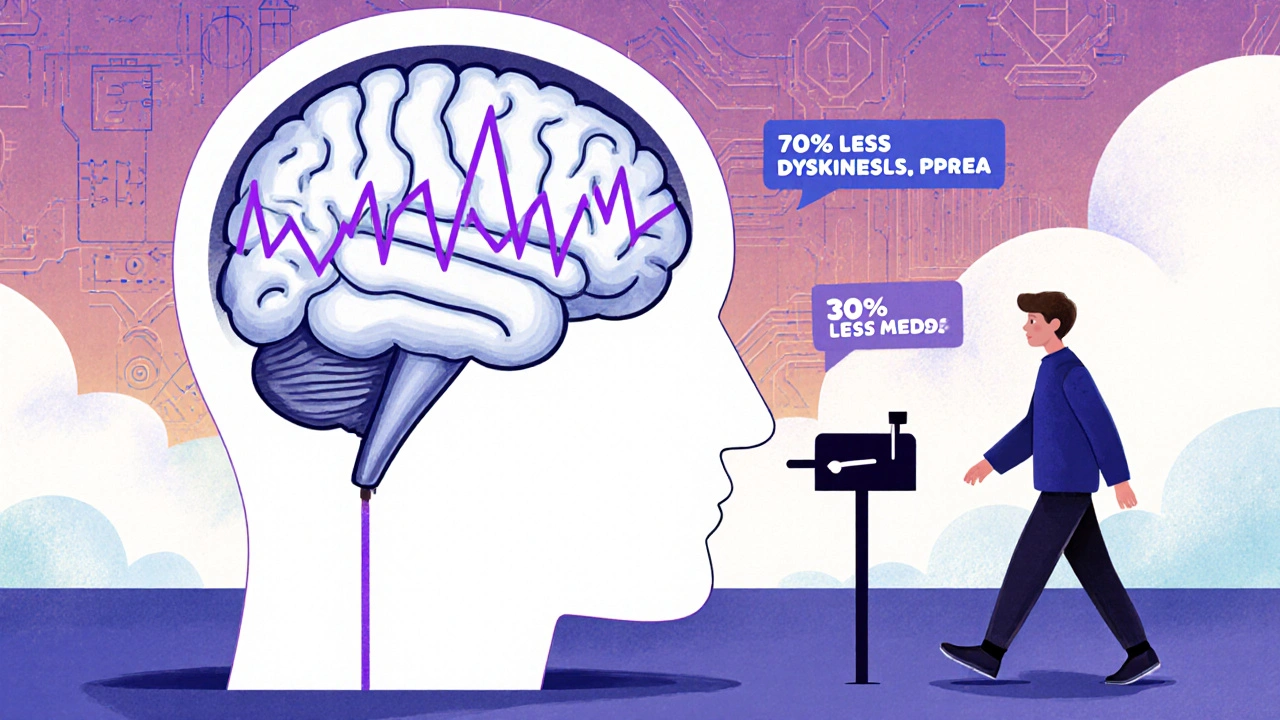

It’s not for everyone. But if you’ve been on levodopa for years and now you’re stuck in a cycle of OFF periods-when the medicine wears off and symptoms return-and then sudden, uncontrollable dyskinesias-involuntary movements when the drug kicks in-DBS can change that. Studies show people can cut their OFF time by 60 to 80%, reduce dyskinesias by up to 80%, and lower their daily levodopa dose by 30 to 50%. The EARLYSTIM trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2013, showed that patients who got DBS earlier in their disease course had a 23-point improvement in quality of life scores, while those on medication alone only improved by 12.5 points. That’s not just a number. That’s being able to get out of bed without help, button your shirt, or walk to the mailbox without fear of falling.

Who Is a Good Candidate for DBS?

If you’re wondering whether you or a loved one might be a candidate, there are clear, well-researched criteria. First, you need to have idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. That means it’s the classic form, not something that looks like Parkinson’s but isn’t-like progressive supranuclear palsy or multiple system atrophy. Those conditions barely respond to DBS at all.

The biggest red flag is if your symptoms don’t improve when you take levodopa. If you don’t get better after a dose, DBS won’t help much either. The rule of thumb? You need at least a 30% improvement on your motor scores (UPDRS-III) after taking your usual levodopa dose. That’s not just feeling a little better. That’s noticing your hand stops shaking, your steps get longer, your voice gets louder.

Then there’s time. Most centers require you to have had Parkinson’s for at least five years. That’s not arbitrary. It’s because you need to have developed clear motor complications-fluctuations and dyskinesias-that meds alone can’t manage anymore. Getting DBS too early, before those problems show up, doesn’t usually help. Getting it too late, when you’re struggling with falls, balance issues, or dementia, makes it risky and less effective.

Cognitive health matters too. If your memory or thinking skills are already noticeably down (MMSE below 24 or MoCA below 21), DBS can make things worse. It doesn’t cause dementia, but it can unmask it or make existing problems harder to manage. People who’ve had trouble with word-finding, planning meals, or following conversations before surgery often report those issues get worse afterward.

STN vs. GPi: Choosing the Right Target

The two most common spots for electrode placement are the subthalamic nucleus (STN) and the globus pallidus interna (GPi). Both work well for motor symptoms, but they have different trade-offs.

STN is the more popular choice. Why? It usually lets people cut their medication dose more-sometimes by half. That means fewer side effects from pills: less nausea, less hallucinations, less daytime sleepiness. But it comes with a cost. Some people notice more trouble with speech, mood, or thinking after STN stimulation. A 2009 VA/NINDS trial found that while both targets improved movement by about the same amount, GPi was better at reducing dyskinesias (70% vs. 46%) and had fewer negative effects on cognition.

So if your main problem is dyskinesias, and you’re already on high doses of levodopa, GPi might be the safer pick. If your big issue is long OFF periods and you want to reduce pill burden, STN could be better. The decision isn’t made by one doctor alone. It’s a team call-neurologist, neurosurgeon, neuropsychologist-reviewing your full history, your symptoms, your goals, and your lifestyle.

The Process: What Happens Before, During, and After Surgery

Getting DBS isn’t a quick decision. It’s a months-long journey. First, you’ll see a movement disorders neurologist who confirms your diagnosis and checks your levodopa response. Then comes neuropsychological testing-four to six hours of memory, attention, and problem-solving tasks. You’ll get a high-resolution 3T MRI to map your brain. Then the team meets. If you’re approved, you’re scheduled for surgery.

The surgery itself takes 3 to 6 hours. You’re awake for most of it. That’s not as scary as it sounds. You’re sedated but conscious so the team can ask you to move your hand, speak, or blink while they test the electrode placement. They use microelectrode recording to hear the brain’s natural signals and make sure the lead is in the exact right spot. It’s precise. The electrodes are only 1.27mm wide.

After surgery, you’ll be in the hospital for a day or two. Then comes the waiting game. The device isn’t turned on right away. It takes 2 to 4 weeks for swelling to go down. Then the real work begins: programming. It’s not like setting a thermostat. It’s trial and error. You’ll come back every few weeks for months. The clinician adjusts voltage, frequency, pulse width, and which contacts on the lead are active. Some people need six months to a year to get it just right.

Many patients keep a symptom diary-writing down when they feel stiff, shaky, or off-and bring it to each visit. That’s how the team fine-tunes the settings. Rechargeable batteries last 9 to 15 years. Older ones need replacing every 3 to 5 years. And yes, that means another surgery.

Real People, Real Results-And Real Challenges

Stories from people who’ve had DBS are mixed, but mostly positive. One man on the Parkinson’s Foundation Forum said his OFF time dropped from six hours a day to one. His dyskinesias went from constant to almost gone. He could hold his grandchild again.

But another person on Reddit said, “My tremors are gone, but now I can’t plan my day. Making breakfast takes three times longer.” That’s not rare. Up to 15% of patients report new or worse cognitive issues, especially with executive function-planning, organizing, switching tasks.

Some people expect DBS to fix everything: their balance, their speech, their depression. It doesn’t. Axial symptoms-gait, posture, freezing-are the hardest to treat. DBS helps only 20 to 30% with those. And if you thought it would slow the disease? It won’t. It treats symptoms, not the cause.

There are also physical risks. About 1 to 3% of people have a brain bleed during surgery. About 5 to 15% have hardware problems-a broken wire, an infection, a lead that moves. These often need another operation.

And cost? In the U.S., it runs $50,000 to $100,000. Medicare covers it, but private insurers sometimes drag their feet. Authorization can take months. Not every center has the team to do it well. Studies show hospitals doing more than 50 procedures a year have 20% fewer complications.

What’s Next for DBS? Faster, Smarter, Personalized

The technology is getting smarter. New devices like Medtronic’s Percept™ PC can actually sense brain activity in real time. They pick up on beta wave spikes (13-35 Hz), which are linked to Parkinsonian stiffness. When those spikes happen, the device automatically boosts stimulation-then turns it back down when things calm. The INTREPID trial showed this closed-loop system improved symptom control by 27% over traditional DBS.

There’s also research into using DBS earlier. The EARLYSTIM-2 trial is testing whether people with just three years of Parkinson’s might benefit more if they get DBS before their symptoms become severe. Early data is promising.

And now, scientists are looking at genetics. People with the LRRK2 gene mutation seem to respond better to DBS-15% more improvement in motor scores. That could one day mean genetic testing helps decide who gets the device.

Even wearables are getting involved. Apple Watch apps now track tremor severity. In the future, that data could sync with your DBS device to make automatic adjustments based on your real-world movement patterns.

Why So Few People Get DBS-And Why That’s a Problem

Here’s the hard truth: only 1 to 5% of people who qualify for DBS actually get it. Why? Many never get referred. Doctors assume the patient is too old, too sick, or too far along. Others think it’s too risky. Some patients are scared of brain surgery.

But the data doesn’t lie. If you meet the criteria, DBS is one of the most effective treatments we have for advanced Parkinson’s. It’s not experimental. It’s been around for over 20 years. The Movement Disorders Society gives it a Level A rating-“Established as Effective.”

And yet, patients often wait too long. They suffer through years of worsening symptoms, thinking there’s nothing else to try. By the time they’re referred, they’ve lost muscle strength, balance, and confidence. DBS can still help, but it’s harder.

If you or someone you know has Parkinson’s and struggles with medication side effects or unpredictable OFF periods, ask your neurologist: “Am I a candidate for DBS?” Don’t wait for them to bring it up. Be proactive. Get evaluated. Even if you don’t end up with the device, knowing your options is power.

Is DBS a cure for Parkinson’s disease?

No, DBS is not a cure. It doesn’t stop Parkinson’s from progressing. It only treats the motor symptoms that respond to levodopa-like tremors, stiffness, slowness, and dyskinesias. It doesn’t help with balance problems, speech issues, or cognitive decline that come later in the disease. Think of it as a tool to manage symptoms, not eliminate the disease.

How long does it take to see results after DBS surgery?

You won’t feel the full effect right away. The device is usually turned on 2 to 4 weeks after surgery, once swelling has gone down. But it takes months-often 6 to 12-to fine-tune the settings. Many people notice big improvements in motor symptoms within the first few programming visits, but optimal results require patience and regular follow-ups.

Can DBS help with freezing of gait or balance problems?

Not very well. DBS is excellent for limb symptoms like tremor and rigidity, but it has limited effect on axial symptoms-gait freezing, posture, and balance. Studies show only a 20 to 30% improvement in these areas. If balance is your main issue, DBS may not be the best option, and physical therapy or assistive devices might be more helpful.

What are the biggest risks of DBS surgery?

The most serious risk is bleeding in the brain, which happens in 1 to 3% of cases and can cause stroke-like symptoms. Infection occurs in about 3 to 5% of cases and may require removing the device. Hardware problems-like broken wires or misplaced leads-happen in 5 to 15% of patients and often need revision surgery. There’s also a small risk of new or worsened cognitive or mood problems, especially with STN stimulation.

How often do you need to replace the battery?

It depends on the device. Older non-rechargeable batteries last 3 to 5 years and require surgery to replace. Newer rechargeable systems (like Medtronic Percept™ PC or Boston Scientific Vercise™) last 9 to 15 years. You charge them externally, usually every few days, for 30 to 60 minutes. Rechargeable systems reduce the number of surgeries but require consistent user compliance.

Can I have an MRI after getting DBS?

Yes, but only under strict conditions. Most modern DBS systems are MRI-conditional, meaning you can have a scan if the machine is set to specific safety parameters (usually 1.5T or 3T, with limited power settings). You must inform the radiology team that you have a DBS device. Scans of the head are safest. Scans of the chest or abdomen may require special protocols or even temporary device shutdown.

What if I don’t qualify for DBS? Are there alternatives?

Yes. Focused ultrasound (Exablate Neuro) is a non-invasive option approved for tremor-dominant Parkinson’s, but it’s usually only done on one side of the brain. It’s not ideal for people with widespread symptoms. Other options include adjusting medications, using infusion pumps (like Duopa), or trying experimental therapies in clinical trials. But none match the broad, bilateral, reversible benefits of DBS for eligible patients.

What to Do Next

If you think you might be a candidate, start by asking your neurologist for a referral to a movement disorders specialist. Don’t wait for them to bring it up. Bring your medication log, symptom diary, and a list of your biggest challenges. Ask: “Do I meet the criteria for DBS? What would the evaluation process look like?”

Find a center that does at least 20 to 30 DBS procedures a year. High-volume centers have better outcomes. Ask if they have a dedicated DBS coordinator, neuropsychologist, and team approach. If your center doesn’t offer it, ask for a referral to a university hospital or movement disorders clinic.

DBS isn’t a last resort. It’s a powerful tool-for the right person, at the right time. Don’t let fear or misinformation keep you from asking the question.

Sam Reicks

they say dbs is safe but have you seen the fda reports? they bury the complications. my uncle got the device and started forgetting his own kids. now they want to put it in kids. next thing you know, the government will be controlling your thoughts through your pacemaker brain

they dont tell you about the 15% who turn into zombies. watch out for the next phase